By Sharon Omahen

University of Georgia

For eight years, University of Georgia Cooperative Extension

county

agents have used digital images, computers and e-mails to

quickly

diagnose insect and disease problems. Now a UGA team has

installed

their system in Honduras to protect U.S. farmers and

consumers.

Called Distance Diagnostics through Digital Imaging, the

system is

in most UGA Extension county offices statewide. UGA shared the

technology with 12 other U.S. land-grant universities and then

added Honduras as its first international partner.

Port prevention

Two DDDI systems have been set up at the Port of Cortez to

prevent

plant diseases and insects from leaving Honduras.

“This is one of only a handful of U.S. Customs offices set

up

in

ports outside the U.S.,” said Marco Fonseca, a UGA Extension

horticulturist and native Honduran. “A U.S. inspector checks the

shipments, so now agricultural products can go straight into our

market.”

Fonseca says the U.S. benefits are twofold: The nation is

further

protected from plant diseases and insects entering its borders,

and

Americans get fresher imported fruits and vegetables.

“The DDDI system at the port is very valuable in terms of

biosecurity,” he said. “And it expedites the process on

valuable,

perishable products. We need to I.D. pathogens and pests at that

point, not on our shores.”

Inspectors are trained to look for pathogens and pests

common

to

the region. Fonseca says with insect pests, this includes

training

inspectors to recognize all stages of an insect’s life, not just

the adult stage.

Pest barrier

“Barriers like this slow down the movement of pathogens and

pests,”

he said. “It’s a defense system to slow down movement. We

aren’t

going to stop the movement of people, so we have to stop the

movement of pathogens.”

The DDDI systems at the Port of Cortez were two of five

installed

through a UGA partnership with the Zamorano Pan American School

of

Agriculture in Honduras. The other three were set up at the

university, on a rural ranch and in a farm village.

“The extension system doesn’t exist there, so farmers don’t

have

county agents to go to for help,” Fonseca said. “Now there’s a

way

for them to get help from the local agriculture university.”

Jean Walter, a UGA Extension agent in Jasper County, Ga.,

knows how

well DDDI works, pointing to a weed problem she checked in a

farm

pond.

“I took pictures of the pond, close-up photos of the weeds

and then

used the dissecting scope to take magnified photos,” she said.

She

e-mailed the photos to a UGA researcher, who quickly identified

the

problem and recommended how to control it.

Farmers and homeowners like the quick turnaround. “With the

high

price of gas now, we’re seeing a huge increase in the system’s

usage,” she said.

Disaster prevention

At an aquaculture conference in Panama and later during a

church

mission trip in Honduras, Walter got the idea of sharing the

technology with other countries.

“In Panama, I heard farmers talking about the huge loss their

country’s shrimping industry suffered due to white spot virus,”

she

said. “This system could have saved Panama and other surrounding

countries millions of dollars.”

In Honduras, she saw many ways the DDDI system could be

used. “I

know ‘rural poor’ because I’ve seen it,” said Walter, who also

lived in the Philippines for five years. “I know what it’s like

to

not have access to health care for people and animals.”

Walter gained the support of Fonseca and Don Hamilton,

director of

the DDDI program at UGA. What she still needed was funding. That

came from Robert Fowler of Covington, Ga.

Fowler is a trustee with the Arnold Fund, a charitable trust

fund

created by the late Robert O. and Florence T. Arnold. The trust

funds scientific and educational programs that strive to make

life

better for the citizens of Newton County, Ga. and beyond.

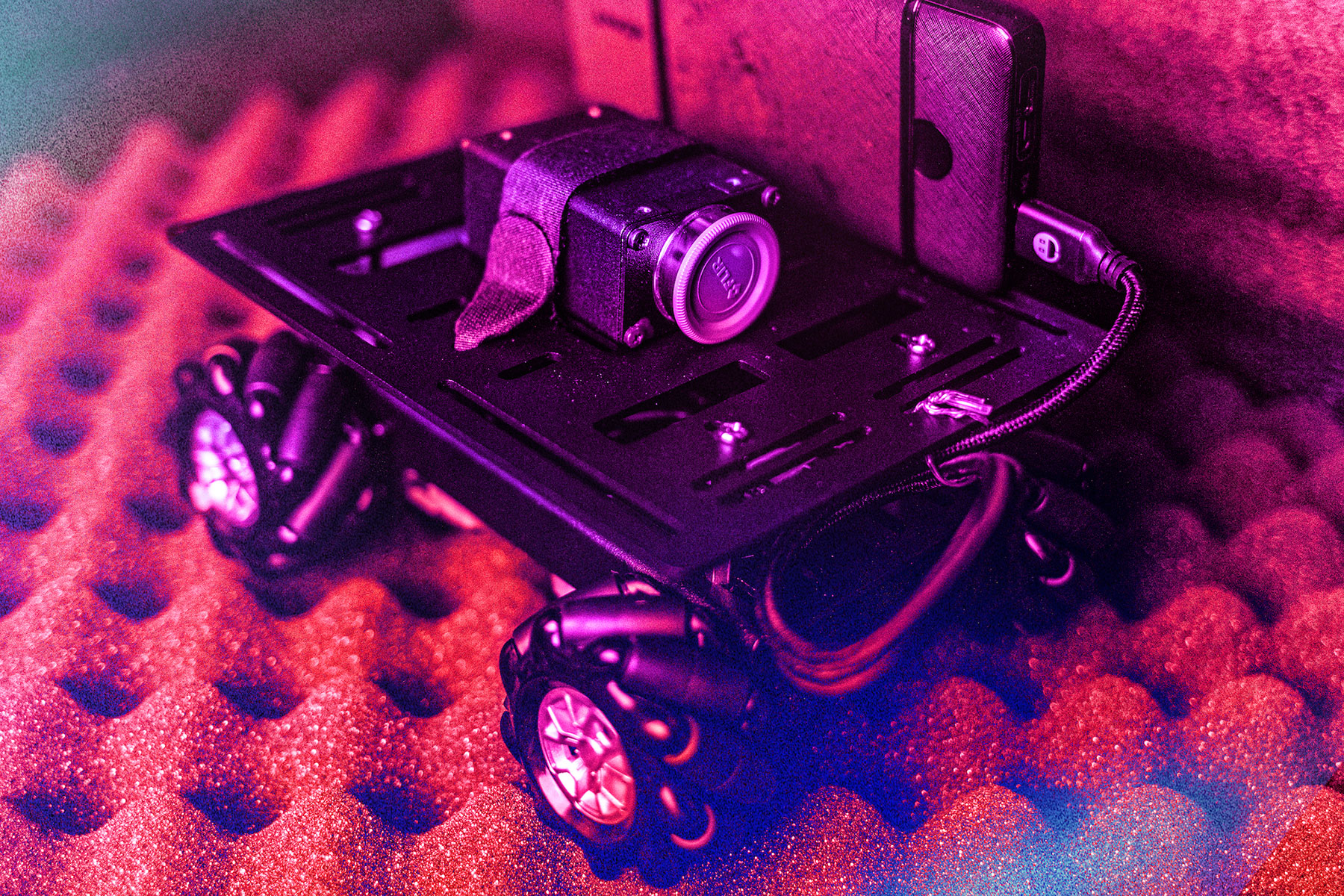

“Each system costs about $5,000 to set up,” Fonseca

said. “This

includes two microscopes, a camera that mounts on the

microscope,

a dissecting scope, a digital camera, a computer and a

printer.”