In 1794, Eli Whitney patented the cotton gin in the United States. Before the invention of this new device, the process of removing cottonseeds from harvested cotton was an intensive, time-consuming process. However, with the introduction of the cotton gin, what previously took days to accomplish could be completed in a matter of hours or minutes. Over the next 230 years, the cotton gin evolved from a simple mechanical device to a highly sophisticated piece of technical equipment, increasing its capacity from 50 lb per day to 250,000 lb per day.

Moving from a manual process to an automated process was a journey that required not only the introduction of new technology but also the awareness and adoption of that technology among producers. University of Georgia Cooperative Extension has played a central role in helping to inform about new technologies, such as the cotton gin, since Extension was officially recognized by the Smith-Lever Act in 1914.

Countless new technologies have been developed to support agricultural and environmental sciences over the past 110 years. And yet, when many of us think about innovation, we might not readily think of these tools, technologies, and techniques that we interface with as Extension professionals on a near-daily basis. It is from this perspective that we must begin to think about innovation not necessarily as something done “out there” but rather something we can support and employ “in here.”

If you were asked to think about the most innovative company you are aware of, what does it look like? What product or service does the company typically provide? What are some of the characteristics associated with the company itself? What about the employees of the company? Many individuals, when asked this question, respond by describing a technology company located in Silicon Valley. These companies are generally very well known in the media and are typically present and visible in our daily lives. Whether they manufacture our phones or run the social media platforms we visit, there is a general perception that innovation looks a certain way. However, the reality is much different.

As Extension professionals, it is important that we are aware of what innovation looks like around us and what our role is to help support and engage in innovative activities. This historical look at the cotton gin shows the power of innovation. To explore how such breakthroughs occur, we must first clarify what innovation truly means.

Defining Innovation

According to the dictionary, innovation is defined as: 1) a new idea, method, or device (novelty) and 2) the introduction of something new. Depending on your answers to the previous set of questions related to what an innovative organization looks like, these dictionary definitions might be somewhat surprising.

At the most fundamental level, innovation is simply something new. This might appear contradictory to the way we typically hear innovation referred to in the media and the way we might personally think about the term. Before beginning to address the fundamental characteristics of innovation and how we can better support and engage in the innovation process as Extension professionals, it is important to ensure we have a robust understanding of the concept.

For example, you will notice that the definition does not include the requirement for the innovation to be of a certain size, have a minimum level of impact, or have a minimum level of adoption. It is critical to embrace this definition to ensure you have the proper mindset to help support you in developing your innovation capacity. If we do not take the time to proactively define and embrace the core of the concept, we might find it difficult to reconcile our individual perceptions with the recommended steps to improve. Having established a clear definition of innovation as “something new,” we can now examine how to prepare ourselves to fully embrace the innovation process.

Preparing for an Innovation Mindset

As Extension professionals, we have the opportunity to work with a variety of stakeholders, as well as help to address some of the most important critical issues that they are facing. Depending on your specialization, you might have deep expertise in a particular area. For example, if you are an expert in growing cotton, you have probably completed all of the necessary coursework and certifications to serve as an expert and professional and are able to provide guidance and advice to producers who might have questions about the best way to grow cotton in a particular environment.

If you were approached by a new producer who was having difficulty getting his cotton crop to germinate and grow successfully, one of the first areas that you might investigate is the preparation the producer was undertaking in their field. After visiting their farm, you find that the producer was scattering seeds on a field covered in weeds, and there was no attempt to create a suitable environment for the cotton seeds to be planted in—that would probably be one of your first recommendations. Prior to planting, the field needs to be prepared. The same mindset applies to innovation more broadly. Before we can effectively engage in the innovation process, we have to be prepared.

To help assess how prepared we are, it can be helpful to go through a quick mental checklist. Specifically, you might want to ask if any of the following internal narratives are playing: I don’t have good ideas! Other people are better than me! What if I fail? Been there, done that! These internal narratives essentially serve as unprepared fields. No matter how much you want to innovate, the conditions simply aren’t going to be supportive.

The good news is when we are aware of some of these tendencies and focus on them, we can work to have our thoughts, rather than being had by them. From a neuroscience perspective, one of the most important conditions to facilitate success in any new area is a belief in our ability to be successful. Therefore, when we consider our thoughts, we can help to redirect them and to ensure that we are creating the appropriate conditions for success.

Are we more open or more closed? If we are more closed, we likely will find innovating difficult, if not impossible. We should be in an open mindset to facilitate the innovation process. Redirecting negative, or closed, internal narratives into positive and open narratives is a critical first step. Once we have identified and addressed our internal narratives, the next step is to actively cultivate practices that drive innovative thinking.

| Closed | Open |

|---|---|

| I don’t have good ideas. | My ideas don’t have to be perfect—the key is to try. |

| Other people are better than me. | Everyone has to start somewhere—experts today were beginners at some point. Colonel Harland Sanders began franchising KFC when he was in his 60s, proving there is no “too late” to start. |

| What if I fail? | Remember the definition of innovation: It is just something new. As long as you meet that standard you are not failing! |

| Been there, done that. | It is impossible to step in the same stream twice—chances are conditions have changed. It took Thomas Edison over 2000 versions of the lightbulb before he found the one that worked. |

Cultivating an Innovation Mindset

Continuing with our cotton example, once you identify that the fields were not properly conditioned to support the seed planting, you would likely recommend taking the necessary steps to improve the conditions. For example, you might suggest eliminating weeds, tilling the field, fertilizing, and ensuring that the seeds are planted at appropriate depth and spacing for the soil type. Once planted, you might also suggest ongoing maintenance. For example, it might be necessary to apply fertilizer, pesticide, herbicide, irrigation water, and so forth. Although some seeds might grow perfectly and require no more effort than simply planting them, as a plan, this is typically insufficient.

The same approach is necessary when thinking about cultivating an innovation mindset. If we have effectively addressed the internal narrative barriers that may exist, the next step is to begin cultivating an innovative mindset. Just as ongoing field maintenance is important for a healthy crop, regularly practicing new thinking techniques is important for developing a robust innovation mindset.

To cultivate an innovative mindset, there are many different approaches that might work for you. For example, some individuals might be able to sit down with a blank sheet of paper and simply generate a long list of potential innovations on the spot. However, for many of us, the idea of the blank page is very intimidating. Rather than setting vague and nonspecific targets for ourselves, crafting very clear goals can help facilitate the process.

Just like any new activity or behavior, starting small and putting in consistent effort over time is the key to building momentum and developing a habit. Therefore, a recommendation is to give yourself a very specific task and target that you will commit to undertaking daily.

The test of divergence described by Malcolm Gladwell in his book Outliers is a great place to start. In essence, individuals are given a picture of a common item and then asked to list as many potential uses for that item as possible. This is also known as the brick and blanket test. Some individuals can generate dozens of alternate uses for either a brick or a blanket, well beyond the common usage for each. However, what researchers have found is that almost everyone is capable of improving their performance in the test of divergence if they put in effort and practice.

One recommendation is to schedule 5 min a day thinking of new uses for a common item that you engage with daily. It might be your pen, water bottle, notepad, calculator, etc. The key is to identify something that you typically use in a very set manner and spend approximately 5 min thinking of alternative uses for the item. You might consider setting a goal for yourself of five uses in 1 min, then another five in the next minute, and so forth. In this way, you have a very specific target and framework to facilitate the innovative thinking process.

By consistently completing the divergence test, you are establishing the environment necessary to think about innovation in a broader context. Having developed stronger creative mindsets through consistent practice, we can now shift from generating possibilities to putting them into action in real-world settings.

You can use this divergence test framework for your practice:

Item:

Minute 1

- Use 1:

- Use 2:

- Use 3:

- Use 4:

- Use 5:

Implementing the Innovation Mindset

As we become more comfortable and confident in developing innovative ideas, the next stage is to look for opportunities to expand these skills into new areas. Let’s continue with our cotton analogy. At this point, the seed has germinated, sprouted, and is in the primary growth stage before the cotton slowly emerges and can be harvested. There are still upkeep and maintenance tasks that are required to ensure the cotton harvest is maximized.

Similarly, when developing an innovation mindset, it’s crucial to think beyond the fundamental mindset and cultivation phases. There can be many different characteristics involved in implementing an innovation mindset, but for simplicity, it might be best to think about the importance of asking good questions. Sometimes the nature of the situation lends itself to a very logical conclusion.

Recalling Eli Whitney and the cotton gin, moving from a manual to a mechanical process required asking how things could be done more efficiently. While we might not find ourselves in situations where we have as fundamental an opportunity for innovation as moving from manual to mechanical processes, using the same questioning techniques can help to identify opportunities.

Jim Kouzes and Barry Posner identified “Challenge the Process” as one of the five practices of exemplary leadership in their classic book The Leadership Challenge. The innovation mindset requires the same ethos. Rather than looking at what currently is, we need to begin to look for what could potentially be. There are several questions that can help guide this process.

| Question | Intent |

|---|---|

| What would happen if our assumptions about the _____ condition change? | Are we limiting ourselves to an existing activity rather than looking at a broader process? For example, do we have to use paper-based registrations or could we use online registration if we had the technology to do so? |

| Is there the possibility that _______ could happen? If so, what would be the consequences? | Are we limiting ourselves to what is known? An example is considering the consequences of moving programming online because of COVID-19 in a very short period of time. |

| Is there an issue of resources or expertise? | What is the main constraint? Identifying the underlying cause of a situation can sometimes identify unexpected sources. |

| Are there any steps in the process that we can eliminate? | Efficiency is a great place to look for innovation. |

These are not intended to be a definitive list of questions but rather a set of example questions that can be used to help catalyze and begin the process. Asking great questions can be extraordinarily valuable to finding innovative solutions. As we become more comfortable with the process of questioning and challenging the process, and therefore implementing the innovation mindset, we become ready to more effectively embrace innovation on a regular basis. Yet, fully embracing innovation requires ongoing dedication. To see lasting impact, we must invest steady effort in refining and sustaining these new ideas, similar to nurturing a growing plant.

Effortful Practice and Innovation

In the fall, if the preparation, cultivation, and care of the cotton plant were successful and we had favorable weather conditions, it is now time to begin harvest. Similarly, with innovation, all of the preliminary steps are intended to develop a level of awareness, confidence, and self-efficacy to prepare us to actually implement innovative practice. As Extension professionals, we have the opportunity to help others on a nearly daily basis. When we look for opportunities to engage in innovative practice to help improve our efficiency and effectiveness in serving our stakeholders, this can be tremendously powerful. Using the preceding frameworks, we can adapt them to opportunities for innovation.

The innovation framework is a synthesis of the previous steps in a very focused and applied manner. First, it’s important to ensure that you are in an open mindset to be aware of and look for opportunities to innovate. Once identified, the context or nature of the situation should be described in as much detail as appropriate. For example, this might be a very high-level description of a set of activities that were recently experienced, such as reflections following a county fair.

Next, before jumping to potential innovations and solutions, it is important to challenge the process and ask relevant questions. Asking a range of questions can help to ensure that potentially important information is not accidentally overlooked.

Once we have asked and answered important and relevant questions, the final step is to identify specific suggested actions. Depending on the nature of the situation, it might be appropriate to have only one or two suggested actions. In other cases, it might be necessary to include more than five. The framework is intended to be a guideline, not necessarily a strict template.

Now that we have a guiding structure in place, we can examine specific examples to see how this framework operates in real extension scenarios.

| Context: [Brief description of the situation] | |

| Questions | Response |

|---|---|

| What would happen if our assumptions about the _____ condition change? | |

| Is there the possibility that _______ could happen? If so, what would be the consequences? | |

| Is there an issue of resources or expertise? | |

| Are there any steps in the process that we can eliminate? | |

| Suggested Actions | |

| 1. | |

| 2. | |

| 3. | |

| 4. | |

| 5. | |

Application of the Innovation Framework

The innovation framework is intended to be practical and useful. There are many different books that have been written about innovation, and these can help to provide much greater levels of depth and detail regarding some of these high-level concepts.

The examples below detail how you might think about using the framework in various Extension settings to assist in implementing innovative ideas in the work that we do.

Example 1

Context

All county fair registrations are submitted in paper format. The entries are then entered by county staff into an online database.

| Questions | Response |

|---|---|

| What would happen if our assumptions about the need to use paper-based entries condition change? | Although paper-based entries have been how entries have always been submitted, there is no policy preventing a move to online entries. |

| Is there the possibility that moving to online entries could happen? If so, what would be the consequences? | Based on a quick poll of advisory board members, there is support for moving to the online entry system. |

| Is there an issue of resources or expertise? | There is expertise at the state level; however, we don’t have the staff, time, or resources to build a system at the county level. |

| Are there any steps in the process that we can eliminate? | Moving from paper-based to online will eliminate at least four steps: 1) receiving mailed entries; 2) opening entries; 3) manually entering data; and 4) confirming accuracy of entered data. |

Suggested Actions

- Propose a pilot of online entry for select fair events.

- Secure support from the state office to help develop the online-entry interface.

- Test and gather feedback from stakeholders on the system prior to launch.

- Roll out to the full fair, pending positive pilot results.

- Share best practices and lessons learned with other counties regarding online entries.

Example 2

Context

There is a limited number of participants attending a healthy cooking class in person.

| Questions | Response |

|---|---|

| What would happen if our assumptions about the time and location conditions change? | There is no reason why the cooking class has to be held in the location it always has been. The timing is limited based on other groups using the cooking space. |

| Is there the possibility that no one attending could happen? If so, what would be the consequences? | Given the decrease in participation, this is a possibility. If this happens, it will not be possible to maintain and offer the program. |

| Is there an issue of resources or expertise? | Neither—the content and instructor are available. |

| Are there any steps in the process that we can eliminate? | Rather than have the cooking class require attendance at all sessions, the class adapts to a “drop in” format in which individuals join when they are able to. This would eliminate the need to maintain registrations and reduce the paperwork for participation. |

Suggested Actions

- Modify cooking class time and location. Offer a session during the day and one in the evenings. Track attendance at each.

- Provide ‘drop in’ participation options. Focus on participation and then look to increase involvement.

These examples illustrate how the innovation framework can assist in our daily innovation practices.

Summary

Innovation is a common term used in both professional and social situations. Despite the common use of the term, it is important to remember that an innovation is simply something new. By this definition, we can all be innovative and bring new ideas forward. This is particularly important for us as Extension professionals, as we need to be constantly monitoring and adapting to the needs of our stakeholders.

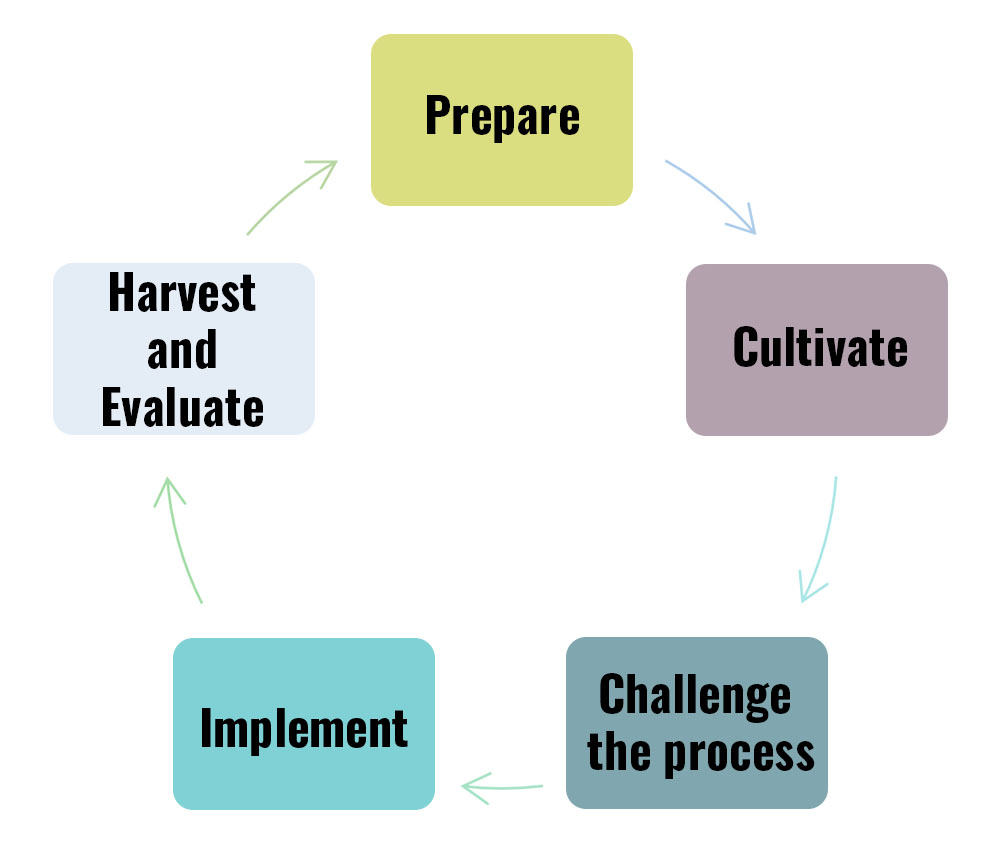

Using a structured approach and framework can be helpful to equip us with the confidence we need to look for new ideas and solutions. As a final visualization of this approach, Figure 1 details how preparing, cultivating, challenging, implementing, and evaluating form a continuous cycle in the innovation process.

- Prepare the Field (Mindset)

- Identify and address negative internal narratives (e.g., “I don’t have good ideas.”).

- Shift to an open mindset, believe in your potential to innovate.

- Cultivate Innovative Thinking

- Practice the test of divergence daily (e.g., list alternative uses for everyday items).

- Develop creative habits and challenge your usual thought patterns.

- Challenge the Process

- Ask probing questions (e.g., “What if our assumptions changed?” “Is there a step we can eliminate?”).

- Look for inefficiencies or outdated practices that could be modernized.

- Implement the Innovation Mindset

- Apply structured frameworks (e.g., the innovation framework).

- Pilot small changes, gather feedback, and refine.

- Harvest and Evaluate

- Assess results and measure impact (like harvesting a successful crop).

- If successful, share best practices and adopt more broadly.

- If not, revisit earlier steps, refine the idea, and try again.

References

Ackoff, R. L. (1981). Creating the corporate future: Plan or be planned for. Wiley. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Creating+the+Corporate+Future%3A+Plan+or+be+Planned+For-p-9780471090090

Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10, 123–167. https://web.mit.edu/curhan/www/docs/Articles/15341_Readings/Group_Performance/Amabile_A_Model_of_CreativityOrg.Beh_v10_pp123-167.pdf

Amabile, T. M. (1998). How to kill creativity. Harvard Business Review, 76(5), 77–87. https://hbr.org/1998/09/how-to-kill-creativity

Bessant, J., & Tidd, J. (2015). Innovation and entrepreneurship (3rd ed.). Wiley. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Innovation+and+Entrepreneurship%2C+3rd+Edition-p-9781119088752

Brown, T. (2009). Change by design: How design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation. Harper Business. http://dx.doi.org/10.23860/MGDR-2019-04-02-08

Catmull, E., & Wallace, A. (2014). Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the unseen forces that stand in the way of true inspiration. Random House. https://www.randomhousebooks.com/books/216369/

Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Harvard Business Review Press. https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=46

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. Harper Perennial. https://inspiredbyislam.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/creativity-flow-and-the-psychology-of-discovery-and-invention-mihaly-csikszentmihalyi-z-lib.org_.pdf

D’Andrea, M. (2014). The myths of creativity: The truth about how innovative companies and people generate great ideas. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 14, 107–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2014.09.007

Dweck, C. S. (2016). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Ballantine Books. https://adrvantage.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Mindset-The-New-Psychology-of-Success-Dweck.pdf

Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The story of success. Little, Brown and Company. https://course-notes.org/sites/www.course-notes.org/files/uploads/archive/other/gladwell_malcolm_outliers_the_story_of_success.pdf

Kelley, T., & Kelley, D. (2013). Creative confidence: Unleashing the creative potential within us all. Crown Business. https://ssir.org/books/excerpts/entry/creative_confidence_unleashing_the_creative_potential_within_us_all

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2017). The leadership challenge: How to make extraordinary things happen in organizations (6th ed.). Jossey-Bass. https://www.wiley.com/en-dk/The+Leadership+Challenge%3A+How+to+Make+Extraordinary+Things+Happen+in+Organizations%2C+6th+Edition-p-9781119278979

Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Riverhead Books. https://www.danpink.com/books/drive/

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2007.07.001

Sinek, S. (2009). Start with why: How great leaders inspire everyone to take action. Portfolio. https://simonsinek.com/books/start-with-why/