Think about the following fictitious scenario: Researchers at the University of Georgia have developed a new best management practice (BMP) for increasing cotton yields an average of 25% while reducing fertilizer and pesticide management by approximately 10%. Based on rigorous testing in many different locations around the state, the researchers are very confident their approach will work if adopted according to recommendations. However, to get the maximum benefit, growers must fundamentally change their planting, fertilizing, and pesticide use. Despite all the potential benefits from the new BMP (economic, environmental, etc.), the actual adoption across growers has remained very low. Based on a survey at the annual cotton field day, only 5% of growers have adopted the new BMPs.

After the field day, the research and Extension team meet to discuss what might be contributing to the low adoption rates. Although several potential reasons for the situation are discussed, the team ultimately determines that one of the main factors for low adoption is that there is no training available for growers to learn about the new BMPs and how to implement them properly. The team also discusses how traditional training approaches, such as field days and in-person workshops, are attracting fewer and fewer growers. Therefore, the team decides it is necessary to create a set of online learning modules for growers to learn about the new BMPs.

Although the team is committed to the new BMPs and confident an online training program will help, the main challenge is deciding where to begin. There is a tremendous amount of technical expertise on the team. However, it is also clear there are some very fundamental questions: Where should they begin? What process will the team use to create the training? How will they make growers aware of the training? How will they know if the training is effective?

Extension professionals frequently wrestle with questions such as these and many others when trying to develop new training materials, particularly online training. One of the most fundamental responsibilities for Extension professionals is to help bring farmers, families, communities, and other stakeholders the latest research, innovations, and best management practices for their lives and livelihoods. However, for many of us, maybe we find ourselves in a challenging situation—perhaps not too unlike our fictitious example above.

We are passionate about our science and experts in the technical aspects of our roles. We know our information can help our stakeholders; however, we might struggle with creating high-value, high-impact online training materials. This bulletin introduces you to a very effective approach to creating training materials. Although we focus on online learning development in this bulletin, the approach works well for both offline, more traditional in-person training, as well as newer models of online learning.

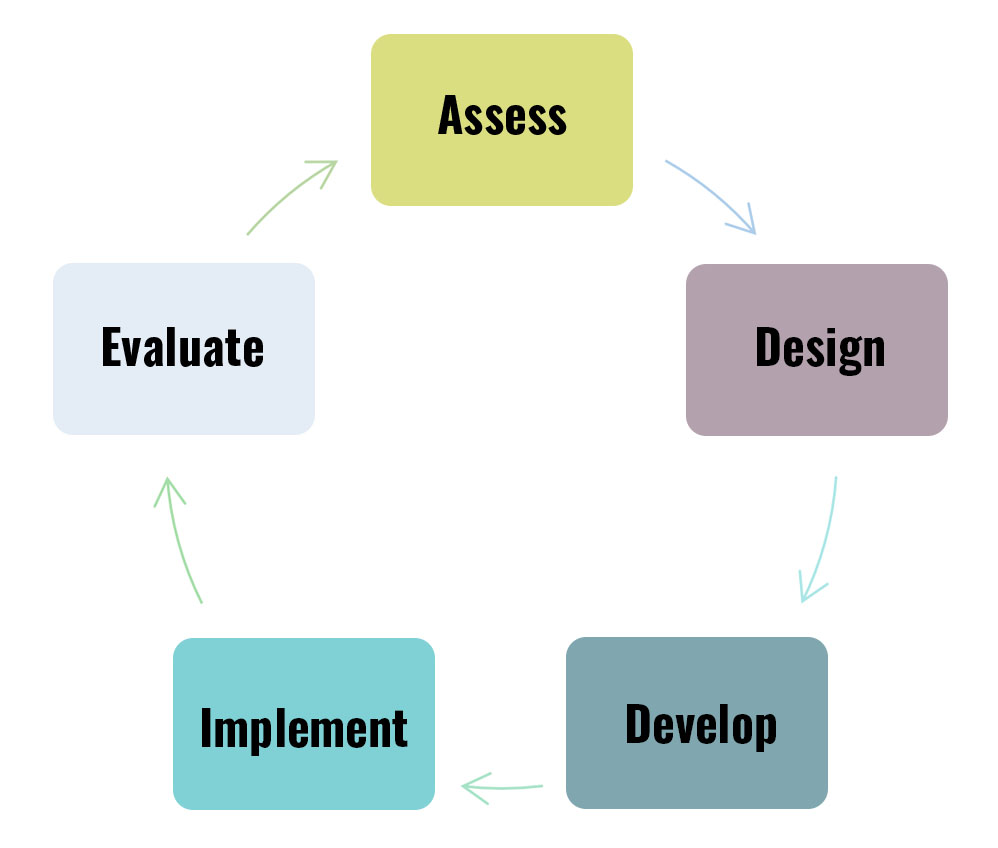

This brings us to the key question: Where do we begin when creating a new online training program? The good news is that a straightforward yet powerful framework exists to guide our efforts. In the next section, we’ll introduce the five-step ADDIE model, which helps you systematically plan, develop, and evaluate training solutions for greater impact.

Introducing the ADDIE Framework

Although there are a wide variety of instructional design frameworks and approaches available, one of the most flexible and adaptable to most instructional situations is called ADDIE. The ADDIE framework has been used extensively across a range of different industries and situations, including Extension.

The strength of the framework is in its simplicity: analyze (or assess), design, develop, implement, evaluate (ADDIE). Each step of the framework includes a discrete set of steps that then integrates into the next. We’ll use the introductory scenario to go through the process from start to finish. Of course, not every situation is going to look the same or have the same requirements. This bulletin provides some examples and guidelines, so think about how you might be able to use this information to support your specific needs.

Step 1. Analyze or Assess

Generally 5%–15% of the Project

After the meeting, the team identified a clear need for the training. They were also able to identify some of the needs of their intended audience—including the need to develop an online training. Frequently, this might be the beginning and end of the initial planning and assessment process. As professionals, we rely on our experience and expertise to make decisions and provide recommendations daily. Using this tacit knowledge is what allows us to quickly and efficiently help a range of stakeholders. However, when we find ourselves starting a new training development project, these insights can sometimes act as blind spots to the needs of those we are hoping to teach. As Mark Twain once famously quipped, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” In other words, what makes us effective in our role as Extension professionals can actually be a barrier to effective training development.

1.1. Goal of the Training

From this perspective, one of the very first steps associated with training development is to ensure the intended outcome from the training is very clearly identified. Is the goal to increase adoption of new technologies? Is it to increase knowledge about important new regulations? Or maybe is it to decrease the number of preventable injuries on the farm? Clarity about the goal of the training should be your first step.

1.2. Available Resources

From a very practical perspective, assessing what resources are available to support the training should be one of your next steps in the process. Although it can be a valuable exercise to think about what training would be ideal to develop without any constraints or practical considerations, from an operational perspective this is generally not the way most training is developed. It is common to have multiple projects and priorities and finite budgets. Understanding these constraints can help to ensure the project is valuable and realistic. There are a wide range of potential resources that you may want to assess and consider:

- Financial resources: Is there a budget to support the project? What about the long-term hosting of the online training?

- Human resources: What is the expertise available to help support the project? Does the team have the necessary technical insights? If not, where can you get the expertise required?

- Existing trainings: Are there existing trainings that could be adapted to the new format? For example, is there an existing curriculum developed for in-person training that could be modified to be delivered in an online format? Is there a commodity organization or professional organization that provides access to the type of training you have in mind?

- Online platform and technologies: Is there a preferred online training platform for delivering training to your audience? Think about what will integrate well with existing technological platforms. Confirm your access to online technical platforms and technologies at this time. A few examples include:

- content development software, such as Canva and PowerPoint;

- audio and/or video production software, such as WeVideo;

- WordPress or other stand-alone blog sites;

- integrated learning management systems (LMS) with content delivery, such as Canvas;

- video hosting sites, such as YouTube and Kaltura; and

- specialized software or technology such as video, screen mirroring, etc.

1.3. Audience

Once you define the training goal and understand some of the practical considerations (available resources) associated with the training, the next step is to clearly define your audience for the proposed training. What are the characteristics of this group? Knowing who you are trying to reach is important and should be one of the first steps you complete. This information will then inform future steps in the process.

What are the characteristics of your ideal learner?

- How old are they? Obviously, a training intended for experienced farmers should be very different than a training for elementary school-aged children. As Extension professionals, we often work with a wide range of audiences. However, training needs to be age- and experience-appropriate. This is one of the unique aspects of Extension that may not always apply to other contexts.

- What experience does this group typically have? Is there a base level of knowledge you can anticipate? Some learners will quit training if they feel it is too basic, while others will quit if the content is too advanced.

- What motivates the learners? Do you know why they are completing the training? Is it something that has the potential to improve their profitability, or perhaps decrease the amount they spend on groceries each month? Is this training optional or mandatory?

- What are some of the technical capabilities of learners? This is particularly important as it relates to online training. Technologies, like video, can be very engaging; however, if your audience has no access to broadband, many of these capabilities will be inaccessible. Similarly, how comfortable are your learners in using different hardware and software necessary to complete the training? A reasonable guide is to develop materials that are accessible by at least 75% of your learners (in the academic world, this may be thought of as addressing the needs of the top three quartiles within your potential population). Although it might be necessary to provide training accessible to 100% of potential learners, acknowledging the balance between engagement and access is important. (Note—you may want to also consider whether your training will be free or paid, as this might impact how accessible the training should be).

- Do any learners require assistive technologies, such as screen readers, captions, or alternative text for images? You can refer to the University of Georgia guidelines for accessibility requirements: https://oit.caes.uga.edu/new-federal-rule-on-digital-accessibility/.

- How do issues like limited broadband, older devices, or language barriers affect learners’ ability to access the training?

- What are the specific gaps in knowledge that the training needs to address? All the above questions can serve to answer aspects of this question. However, it is important to pause and ask the question—what is it that we don’t know or aren’t thinking about? Generally, there is a relationship between project time invested and the resources required to modify it; the further you are into the process, the more costly it is to make a change. Therefore, asking the right questions during the initial stages of the project can save substantial time and effort later.

1.4. Needs Assessments

One of the most effective ways to go about collecting and organizing the information associated with the “Analyze/Assess” phase is through a needs assessment. As the name implies, the needs assessment is an opportunity to identify the needs of a group. A great way to think about needs assessments is a way to capture “as is” and “to be” states. Where is the audience currently, “as is”? Where should the audience be, “to be” or the goal?

We use needs assessments frequently in Extension work. From a program development perspective, we might conduct a needs assessment to understand where there are gaps within our current programmatic portfolio. In the training development process, they are useful to accomplish the same thing.

Although beyond the scope of this bulletin, there are many different types of needs assessments, such as gap analyses and appreciative inquiries. Different methodologies can provide different levels of statistical rigor and insight. Quantitative approaches might focus on descriptive statistics or Borich (knowledge and skill) analyses, whereas qualitative approaches might be more appropriate to gather open-ended question responses. Here are a few considerations regarding needs assessments:

- How does the training needs assessment fit into your broader Extension program? Finding opportunities to reduce redundancy and improve efficiency are always recommended.

- Think about the results of the resources section above—how much time and money are available for the project? How much is appropriate to dedicate to the needs assessment? Generally, 5%–15% of the entire project time (and budget) is expected to be dedicated to the “Assess” stage. What resources are necessary to gather the information you need to move forward with the process? Developing a robust needs assessment can provide excellent insights; however, committing too many resources to initial data gathering can be problematic later. A target of 5%–10% of your resources dedicated to the needs assessment might be a good starting point, though each project is different, so be sure to adjust up or down as needed.

- Do you have access to your ideal learner? In training development, one of the classic parables is that of a person who has lost their car keys in a huge parking lot at night. When asked where they think they lost their keys the individual points to a dark corner of the lot. When asked why they are then searching for their keys so far away from where they lost them, they reply, “There are no lights over there and I couldn’t see anything, so I came over here under this streetlight to look.” Sometimes we do the same thing during needs assessments—easily accessible audiences may not be what we really need. Use the ideal learner work you completed to make sure the needs assessment is representative.

- Plan some contingency time to make sure you understand the results. The needs assessment should not be a confirmation exercise. When done properly, it can provide novel insights that are tremendously valuable and can help to guide the entire project. In this regard, they can act as a safeguard against our own professional experience and intuition. Although your experience is valuable, be open to what the results say—perhaps what you thought were primary needs are symptoms of more fundamental gaps. Use this time as a reality check on what you expected versus what was actually observed.

- Use a flexible approach to the needs assessment process. Not all projects will require a formal needs assessment, whereas others will greatly benefit from a more rigorous process. Regardless of how it is collected, understanding the needs of your ideal learner will be extremely important as you move forward with the process.

Given the previous cotton BMP scenario, perhaps the team’s needs assessment revealed that most growers were aware of the new practice but lacked confidence in how to implement it. This finding also showed that many growers were seeking online training options they could access at their convenience. By understanding these specific knowledge gaps and platform preferences, the Extension team could tailor the upcoming training to address both implementation know-how and flexible scheduling.

1.5. Wrapping Up

At the conclusion of the “Assess” phase you should now have a very clear:

- Goal for the project,

- Assessment of available resources,

- Manner in which the online training will be delivered (technical platform),

- Definition of the ideal learner, and

- Systematic assessment of learner needs (does not always need to be a formal needs assessment).

With these needs identified and the scope of the project defined, we’re ready to turn these insights into actionable learning objectives. In Step 2, Design, we’ll determine exactly what learners need to accomplish—and how the training will guide them there.

Step 2. Design

Generally 15%–25% of the Project

At the conclusion of the “Assess” phase you should have a very clear idea of the intent, scope, and resources available. Once you have this information, you are now ready to begin the “Design” phase. In this phase, you will start framing out the actual content.

2.1. An Introduction to Learning Objectives

You should have a clear idea of your training goals coming out of the “Assess” phase. In the “Design” phase, you will take this overarching vision and begin to operationalize it. At this phase, we should be asking what someone should learn because of the training, or what we want someone to be able to do after completing the training. The answers to these questions directly inform the learning objectives. This is also why the “Assess” phase is so critical. Understanding the needs of our learners should directly inform the design of our training.

To help illustrate this process, think about the following: You are in Atlanta and planning to drive to Valdosta. You know your current state, as well as where you want to be—these are our “as is” and “to be/goal” states from the needs assessment. Along the way you will need to stop in Forsyth, Macon, Perry, and Tifton. These are critical points along the journey and will indicate that you are making effective progress. Learning objectives serve the same purpose. It might be helpful to think about learning objectives as follows:

- Terminal Learning Objectives (TLO)—the overarching goals and expectations for the program. These are arriving in Valdosta and the end of your drive.

- Enabling Learning Objectives (ELO)—the supporting and developmental steps throughout the program. These are your stops along the way.

- NOTE: Not all training will need both TLOs and ELOs. Brief, stand-alone online trainings may only need TLOs. The TLO and ELO structure is helpful if you are developing a longer, more sophisticated training that might run from several hours to several days in length. The approach included here is intended to be flexible depending on the needs and ultimate goals of your program.

The good news is that you don’t have to try to develop learning objectives independently. There are some very good models available to help you with the process.

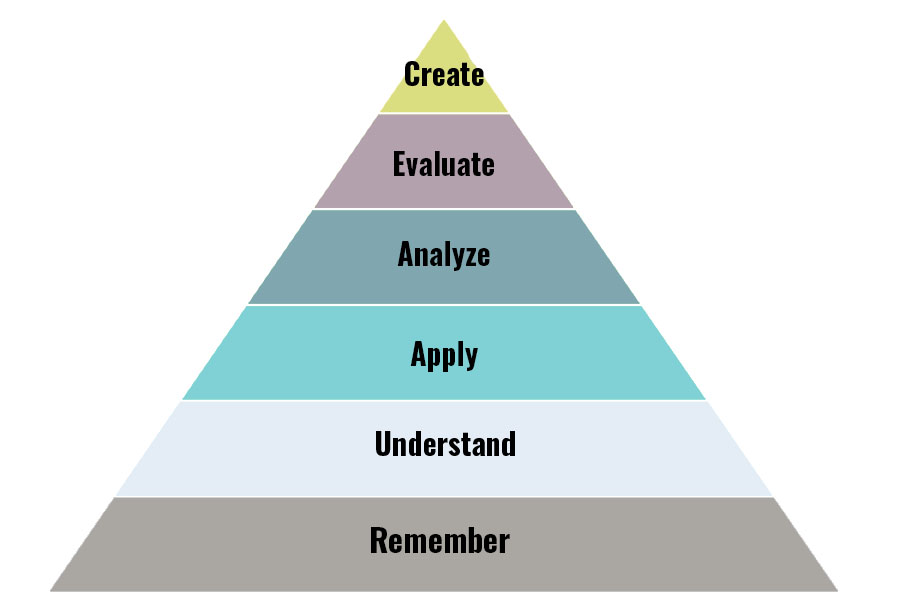

2.2. Bloom’s Taxonomy

One of the most prominent and common ways to develop learning objectives is using Bloom’s Taxonomy. This model provides developmental language to help you create your training learning objectives. As you can see from Figure 2, the model starts with “Remembering” at the foundational level and increases in sophistication and difficulty until culminating in “Create” at the top.

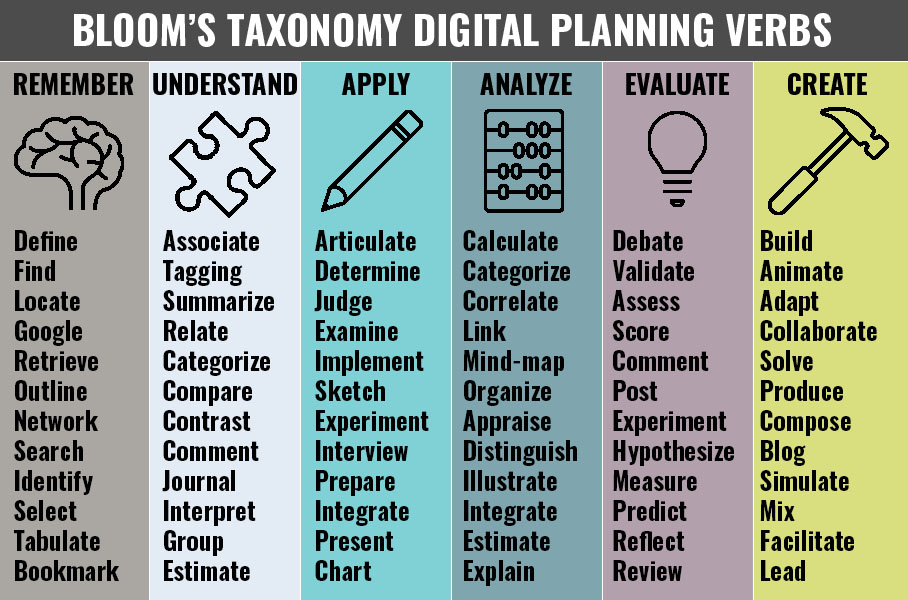

At each level in the model, the amount of learner knowledge and insight increases. Figure 3 provides a list of verbs to use in conjunction with the different levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy. The list is noninclusive but may be helpful and even inspirational when it comes to crafting learning objectives and thinking about potential learning activities for digital delivery.

A recommendation is to use Bloom’s Taxonomy to develop your training’s learning objectives (terminal and enabling) in a coordinated manner. For our example, perhaps the team decides on the following:

- TLO: By the end of this training program, farmers will be able to apply the new cotton best management practices in their fields by correctly implementing the recommended fertilizer application rates, irrigation schedules, and pest control measures.

- ELO 1: Farmers will recall (Remember) the recommended fertilizer application rates, irrigation schedules, and common pest control measures outlined in the new cotton best management practices.

- ELO 2: Farmers can explain (Understand) how proper fertilizer application rates affect soil health and cotton plant growth, including how nutrient availability influences yield potential.

- ELO 3: Farmers can discuss (Understand) the rationale behind the recommended irrigation schedules and pest control strategies, highlighting how these practices minimize resource waste and protect cotton crops from stressors.

2.3. Moving from Objectives to Content Design

It is also important to think about the best way to go about ensuring the training material will be successful in meeting the objectives. This is where your resources assessment will be very helpful. From a practical perspective, it is helpful to think about what is reasonable versus what is ideal. One recommendation is to learn about the abilities and limitations of your technical platform.

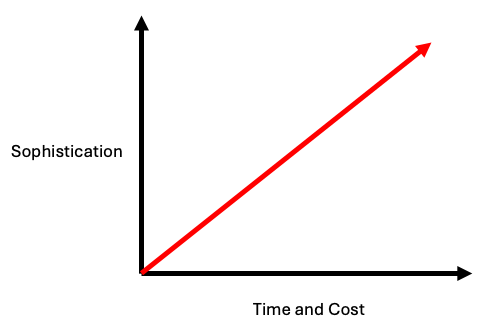

Here’s another analogy to help conceptualize the process: think about building a house (an imperfect analogy, but hopefully helpful conceptually). In the “Assess” phase, we developed blueprints and obtained the necessary permits for the construction. In the objective development stage, we are establishing the foundation (TLOs) and completing the framing (ELOs) for the structure. We are now ready to start “roughing in” the electrical, plumbing, and HVAC systems. We need to plan, measure, and think about how all these systems are going to fit together inside the house. It would not be reasonable to have all your light switches in one room, nor to have all your sinks in another. Keep this in mind when starting to design how your content will support your proposed learning objectives. Also keep in mind, the more sophisticated your training, the longer it will take and more it will cost to develop.

2.4. Content Design Best Practices

Here are some recommendations when thinking about designing your content:

With in-person training, a general guideline is to vary training interaction at a rate approximately equal to the age of your audience.

- For example, working with a class of 10-year-olds, you would probably want to lecture for only 10 minutes at most before doing some other form of teaching—a game, partner work, or other activity.

- For a class of undergraduate students, you might be able to have 20 minutes of lecture before needing to switch learning strategies. For adult farmers you might be able to lecture for 30 to 45 minutes before needing to provide some form of cognitive break (adults generally have a maximum attention span of 15–20 minutes; however, this can vary depending on engagement and norms within a group).

- For online training, a recommendation is to reduce these values by half or potentially by two-thirds. Learner engagement will decrease more rapidly in an online environment when other distractions abound. Interspersing learning interventions more frequently than with in-person training is strongly encouraged.

Each level of Bloom’s taxonomy will have different types of learning interventions. A few examples might include:

- remember: static content, interactive flashcards, multiple-choice knowledge checks.

- understand: short explainer videos, concept mapping, discussion forums.

- apply: scenarios/simulations, guided practice, interactive worksheets.

- analyze: case study comparisons, data analysis, peer debriefing/group discussions.

- evaluate: peer reviews (online presentations and peer feedback), debates, rubric-based projects.

- create: action plan development, create a digital asset or explainer video, prototyping.

For online training, some levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy are easier to develop toward than others. This does not mean it is not possible to address all levels with online training, it just means you will need to be realistic (refer to Figure 3).

- In general, most online training is developed to address remember and understand levels.

- More sophisticated training (such as certifications) may include apply and analyze levels.

- Very sophisticated training (such as online degree programs) may include evaluate and create levels. Each training situation is unique, and these are intended to be starting points rather than formal guidelines.

Think about accessibility for your training. Alternatives such as audio transcripts, captioned videos, high-contrast visuals, and text-based options for interactive activities may be helpful and/or appropriate. Additionally, consider that some learners may prefer or require a text-based alternative to streaming video because of limited bandwidth or the use of assistive technology.

Remember, at this stage you are not developing content, you are designing how everything is going to fit together. This is particularly important if you are working with a team. Think about how learners will be going through the training—will it be available on-demand and as needed? Or will it be provided in a sequence with content building from one session to the next? Planning at this stage can help to make sure your training is comprehensive and cohesive.

Returning to our cotton BMP example, if the overarching goal (TLO) is for growers to successfully adopt the fertilizer, irrigation, and pest control measures, your enabling objectives might focus on recalling the basic BMP guidelines, explaining why the new rates and schedules matter, and comparing results between BMP and conventional methods. Designing interactive modules, such as short explanatory videos comparing yield data, will help ensure farmers not only remember the information but also see its practical value in real-world conditions.

- ELO 1: Farmers will recall (Remember) the recommended fertilizer application rates, irrigation schedules, and common pest control measures outlined in the new cotton best management practices.

- content: static content to provide foundational knowledge.

- content: interactive quiz to provide real time feedback on recall.

- content: static content with images and graphs.

- content: interactive drag-and-drop exercise.

- ELO 2: Farmers can explain (Understand) how proper fertilizer application rates affect soil health and cotton plant growth, including how nutrient availability influences yield potential.

- content: create a short explainer video on content.

- content: present a short case study—BMPs vs. Not.

- content: map concepts—creating an interactive Google image where learners connect fertilizer and pest management.

- ELO 3: Farmers can discuss (Understand) the rationale behind the recommended irrigation schedules and pest control strategies, highlighting how these practices minimize resource waste and protect cotton crops from stressors.

- content: discussion forum where learners respond to questions related to fertilizer application rates.

- content: ask an expert session—live question and answer with project team experts.

- content: reflective journal—learners will record weather information and describe how proposed fertilizer changes would impact their operations.

Obviously, this proposed content is not necessarily accurate; however, it is intended to demonstrate how different learning approaches and activities can be used to achieve different learning objectives.

2.5. Wrapping Up

At the conclusion of the “Design” phase, you should now have very clear:

- learning objectives for the training—terminal and perhaps enabling, depending on training needs;

- objectives that are mapped to specific levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy;

- content that is planned/designed to appropriately support the successful completion of each objective; and

- basic shape and structure of the training.

Having defined our training roadmap—objectives, structure, and activities—the next step is to bring these plans to life. In Step 3, Develop, we’ll craft our content, integrate multimedia, and refine materials for an engaging online training experience.

Step 3. Develop

Generally 30%–50% of the Project

The “Develop” phase is where most of the activities that we typically think of being associated with creating training will actually occur. Now is when we use our technical expertise to share the data, information, and knowledge necessary to support learners in their move from the “as is” to the “to be” state discussed in the needs assessment step. The reason we dedicate 20% to 45% of our time in the “Assess” and “Design” phases is so the “Develop” phase can proceed according to a plan, rather than just randomly.

Remember our house analogy? The “Develop” phase is where we actually install all of the mechanical and living systems necessary to make the rough framework into a livable house. This includes the activities such as installing the electrical and plumbing systems (creating the fundamental learning material that you want to cover—facts, methods, procedures, and so forth) all the way through installing carpet and painting the walls (performing copyediting and revisions to clarify, integrate, and polish the final writing and graphic design).

3.1. Gathering Content

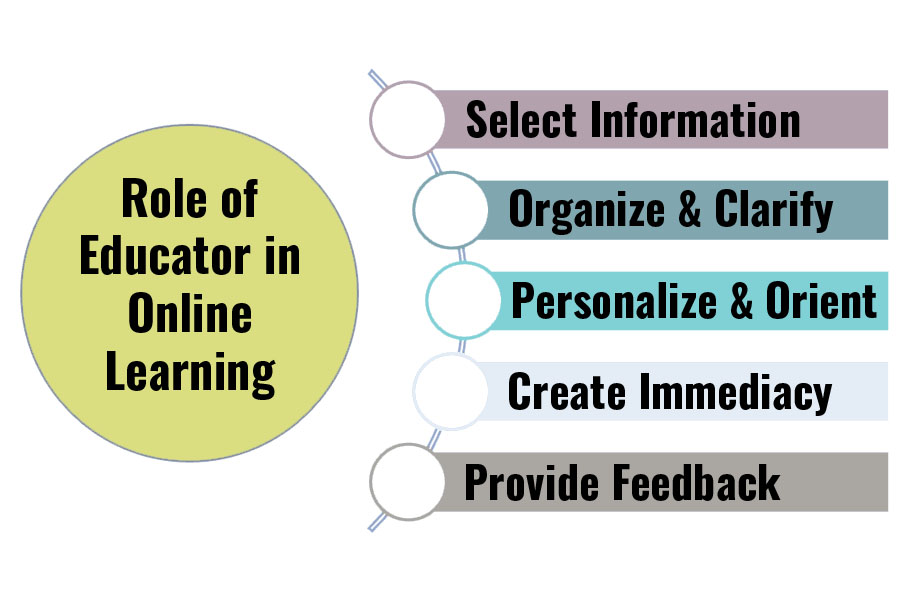

The process of content development is probably something you are already familiar with; as Extension professionals we are both creators and consumers of a wide range of trainings. However, online learning environments have shifted how we think about the role of an educator or facilitator. The role has shifted from the traditional “sage on a stage” to a “curator of knowledge” (See Figure 5). You are selecting the information that your learners are exposed to and packaging it into an educational format.

There are several suggestions to help you with the process:

- Engage experts—you might be the definitive expert on a particular subject. If this is the case, your experience can serve as an excellent starting point. However, if you are not an expert in the focus area for your training, it is important to connect with others. This may involve county faculty and agents directly engaged with stakeholders and production practices, individuals who have a very practical perspective, or it might involve Extension specialists who have a more academic-based perspective. Rather than trying to create content from scratch, engaging experts can be very useful and effective.

- Referring to our scenario, the content gathering process is your opportunity to assemble resources that can best serve cotton growers across the state. Reaching out to the Extension specialists, researchers, and/or agents who were and are engaged in the research and development of the BMPs is a great place to start. They may even share presentations and/or informative videos they have created.

- Refer to the literature—in addition to person-based expertise, academic literature can be a tremendous resource. One of the most important aspects of Extension is the sharing of scientifically grounded information. Using these sources can help ensure your content is accurate and robust. In addition to peer-reviewed academic journals, look for existing Extension publications that might contain useful information. Integrating and adapting (properly cited) existing material can be very helpful.

- Academic literature or Extension publications may contain information that can help your cotton growers understand the changes in the BMPs, trends in production practices, and more. The experts that you engage may be able to provide materials—like research findings, technical papers, and summarized documents—or point you in the right direction.

- Refer to industry publications—sometimes there can be a time lag between when academic articles are published and more contemporary issues. Examine industry or trade publications to identify content that might be relevant and timely. These types of resources are typically published on a more regular basis and, while not as rigorous as peer-reviewed academic journal articles, many are quite accurate and can be beneficial.

- Your cotton growers no doubt subscribe to or access the information that comes out of industry publications like Cotton Grower Magazine or Cotton Farming. In fact, some of the experts you speak with have probably contributed to their content. Tying in information from these sources can show the immediate relevance of your training.

- Plan for the unexpected—gathering content can be both an exciting and overwhelming process. As you begin your research and data gathering, look for unexpected angles or perspectives that emerge. Although you have spent considerable effort in the “Design” phase, remain open to new directions with the training. Perhaps there is an even newer technology that has recently become available. It is probably better to include the latest information in your training rather than developing something that you know will already be outdated once available.

- Think about casting a wide net, within reason—similar to the preceding point, the intent of gathering content is to find sufficient information to support all of your proposed learning objectives and activities from the “Design” phase. However, it is possible to get mired in the searching process. Try to perform a thorough but reasonable search. Using a range of sources will help to ensure you have done your due diligence in making sure your training will be accurate and beneficial. However, it will be impossible to ensure there is not some information that you may miss in the process. This is also acceptable. Finding a balance between accuracy/completeness and efficiency is important—a perfect training that is never completed is less helpful than a very good training made available quickly.

3.2. Integrating Content

After you have completed the content gathering process, the next step is to synthesize and integrate the information you have found. Sometimes this can be a very simple process, but sometimes reconciling different recommendations and suggestions can be challenging. To help with the process, here are a few suggestions:

- Don’t forget about the goals and learning objectives—One of the most powerful tips during the “Development” phase is to ensure that you remain focused on why you are creating the training in the first place. It is easy to become distracted with novel insights and cutting-edge technologies, particularly with online learning; however, these aspects are generally not fundamental; they are often cosmetic. Effective and appropriate content should take precedence over a particular feature.

- Synthesize—During the gathering process, hopefully you identified more than one source for much of the content you will need to achieve your learning objectives. Taking the time to reconcile differences and synthesize multiple sources into a single, coherent narrative is very important.

- Align content with objectives and activities—As you move through the process, you may find that the content you have does not lend itself to the activities you had expected to use. This is fine and expected. Allow the content to lead the process and don’t feel constrained by your initial plans in the “Design” phase.

In the cotton BMP scenario, perhaps the team chose to record short interviews with Extension specialists and veteran growers who had early success applying the new fertilizer rates. These videos, combined with peer-reviewed research summaries, provided a robust set of content. The module walk-throughs also included step-by-step guides to calculating fertilizer needs, ensuring the final training integrated expert knowledge with practical field examples.

3.3. Author and Assemble

Throughout the “Development” phase you have been gathering and integrating content, which is consistent with authoring and assembling. However, it is important to think about the final construction of the online training as well. This is also a good time to think about accessibility—are you considering learners that may have bandwidth limitations or require assistive technologies? Here are a few suggestions for helping with the process:

Aim for 85% completion in your first draft.

- During the integration process, you’ve been adding content and activities to your training. Depending on your preferred style, this might have been a very structured or unstructured process (copy/paste, original writing, some combination, etc.). No matter how you got to this point, it is now necessary to go through the entire training, start to finish, and make sure it is logical, integrated, and consistent. Spend the time to make sure the training is complete and aligned with your design. However, don’t worry about perfection right now.

- Focus on major inconsistencies or issues. If content is missing, add it. If an activity is not working properly, think about replacing it. The training does not need to be ready for learners yet, but it should be mostly complete.

- Again, thinking about our house analogy, this might be the point at which everything but the final painting and trim work has been completed. The house is livable (lights turn on, water runs, and so forth), but it would not be ready for someone to move in quite yet.

Get feedback.

- Throughout the design and development processes, hopefully you have been getting insights and feedback from others. This is particularly important as you are entering the final stages of development.

- In the academic world we might call this “establishing response process validity”, but an easier way to think about the process would be “does the training function like I expect?”

- Recruiting a few learners, ideally individuals not involved in the training development process, to complete the training can provide very useful insights. For example, maybe a link in the training is broken, or one of the quizzes is not auto-grading correctly. Getting an outside, unbiased opinion will be very useful to ensure the training is working as anticipated.

Revise and iterate.

- Once you get feedback on the training, it is important to go back and address all comments and recommendations.

- Plan for more time than you think it will take to address such feedback. Having more time allocated for revisions is a conservative strategy—particularly if you think you might need to go through more than one round of reviews.

3.4. Finalize and Prepare to Implement

After you have assembled, tested, revised, and retested your training, it is now time to move from 85% complete to (close to) 100% complete. No creative work (like training development or writing) is ever 100% complete, so there is no need to hold yourself to a level of perfection. However, the training should fulfill the following requirements:

- functions as expected, and all technology works for learners;

- addresses all copyediting and grammatical corrections; and

- follows a coherent narrative throughout.

3.5. Wrapping Up

At the conclusion of the “Development” phase, you should now have a fully complete online training, ready to implement and make available for learners. A few reminders about this phase:

- Gather information from a variety of credible sources.

- Integrate the content and align it with your design, making modifications as necessary.

- Be sure to plan time to pilot test and revise your training before finalizing.

- Take the time to ensure the training is as complete and correct as possible.

Now that your online training is ready to go, the focus shifts from creation to delivery. During Step 4, Implementation, we’ll cover how to roll out the program, coordinate platform logistics, and make sure it reaches your audience effectively.

Step 4. Implementation

Generally 5%–20% of the Project

The implementation phase for online training can have a wide range of time and technology requirements. However, as a general guideline, this phase tends to be more technical and less creative in nature. From this perspective, implementation generally can be broken into three main stages: prelaunch, launch, and postlaunch.

4.1. Prelaunch

During the prelaunch stage there are several different action items that may be required. Here are a few suggestions:

Platform Preparation—As was covered previously, one of the unique characteristics of online learning is the technology used. Different learning approaches may require more or less support and preparation. For example, if you are using a stand-alone narrated PowerPoint that you plan to host on your program’s Extension WordPress site, you may have only a few technical steps required. However, if you are creating a dynamic and interactive learning environment with audio, quizzes, video, and other activities, you may need to make sure your platform (where the training will be hosted) is enabled to support all this functionality. If you don’t own the hosting platform, work with the individual or organization who does to make sure everything is set prior to launch. This is also a good time to confirm your training and platform support assistive technologies as appropriate. Conducting a technology check to confirm accessibility with someone with relevant expertise can be very helpful.

Marketing—As Extension professionals, an important aspect of our roles is to ensure the information we are providing is accurate, practical, and gets used. Therefore, it is important to think about how we are going to encourage and motivate learners to complete the training. From our scenario, you probably know where the cotton growers go for information. Social media? The Extension office? The local breakfast restaurant? Put your efforts where they will be most effective. There are several different approaches that you may want to consider:

- Social media—This can be a great direct method of connecting with potential learners.

- Newsletters—Extension has several topical newsletters that are sent to interested stakeholders. Using these newsletters to market your training might be a good way to increase awareness.

- Personal network—Connecting with trusted contacts and asking them to help spread the word can be very helpful.

- Ads, flyers, other—There are many different traditional and nontraditional ways in which you might want to market your training. Using creative options may engage learners that you might not otherwise reach.

4.2. Launch

Once your online training goes live, it is now available for learners to complete. This stage is where the time and effort you have invested in the prelaunch activities will be useful. There are a few recommendations for the launch stage:

- Confirm—Once the training has been made available, it is always a good idea to confirm that it is in fact available. Sometimes, depending on the technology and platform, there may be different views available—one for teachers/creators and one for learners. Ensure that learners can view the training.

- Communicate—Based on your prelaunch marketing, hopefully you have been able to create both awareness and interest in your training. Now is the time to make sure learners know the training is available for them to complete.

- Be Prepared—A very common scenario is to have spent extensive time, effort, and resources to assess, design, develop, and then implement an online training course, only to have something go wrong during the launch stage. While all your preparation has hopefully minimized the potential for this situation, it is still important to acknowledge that not everything may go as planned. As Extension professionals, maybe we had rain during the county fair, or schools closed because of weather the day we planned to present a program. These things happen and, likewise, launch-related issues also occur. A recommendation is to consider a soft launch where the training is live but is not actively promoted or publicized. If something doesn’t go as planned, try to be flexible and work toward a solution rather than fixating on why the problem occurred.

For the cotton BMP training launch, perhaps the team partnered with local cotton commissions and county-based personnel to publicize the course via social media, commodity newsletters, and word of mouth. They also coordinated a short virtual field day kickoff, giving growers a chance to ask live questions. By aligning the launch with growers’ usual information channels, more participants were immediately aware of—and engaged in—the new online modules.

4.3. Postlaunch

After your online training is successfully launched and available, it is important to periodically check in and monitor how things are operating. A few associated recommendations:

- Engagement/Completions—On a periodic basis, check to see how many people have completed the training. This is an important indicator of use. This can also help to identify if additional awareness and marketing efforts are required.

- Maintenance schedule—After the course has launched and is available, it is important to think about how frequently it is necessary to update and maintain the content. This is where your expertise will be very helpful. If the content is focused on a fast-moving, unstable content area, such as an invasive species, you may need to update the material on a monthly basis. However, if your content is more stable, perhaps it is necessary to review and update only every 2 years.

- Feedback—The final phase of the ADDIE framework is evaluation, which will be covered in detail in the next section. However, from a postlaunch perspective it is important to be open and receptive to feedback (perhaps proactively provided) about the training. Maybe there is an activity that a learner says is very engaging. Or there is a section of content that a peer tells you is somewhat confusing or out of date. All of this information can be helpful in making sure your course, and potentially future courses, is as beneficial as possible.

4.4. Wrapping Up

The implementation phase represents a fundamental shift—moving from in development to available. Here are a few highlights:

- Don’t forget to prepare for the launch. Is the platform ready? Have you marketed the training?

- During the launch, be sure to confirm that the training is now available for your learners.

- If something goes wrong with the launch, focus on solutions. You can figure out what went wrong later.

- Once the course has been launched, be sure to monitor how it is doing.

With the course now live and available to learners, the time has come to measure its effectiveness and determine whether it meets your training goals. In Step 5, Evaluation, we’ll explore how to assess learner outcomes and gather insights for continuous improvement.

Step 5. Evaluation

Generally 5%–15% of the Project

What does success look like and how will you measure it? Based on all the work you’ve put into assessing, designing, developing, and implementing the training, it is important to make sure you have a process in place to determine if it is successful. As Extension professionals, we are all very familiar and comfortable with the concept and importance of evaluation. It is a way we can gather insights and feedback regarding our efforts and use this information to make improvements.

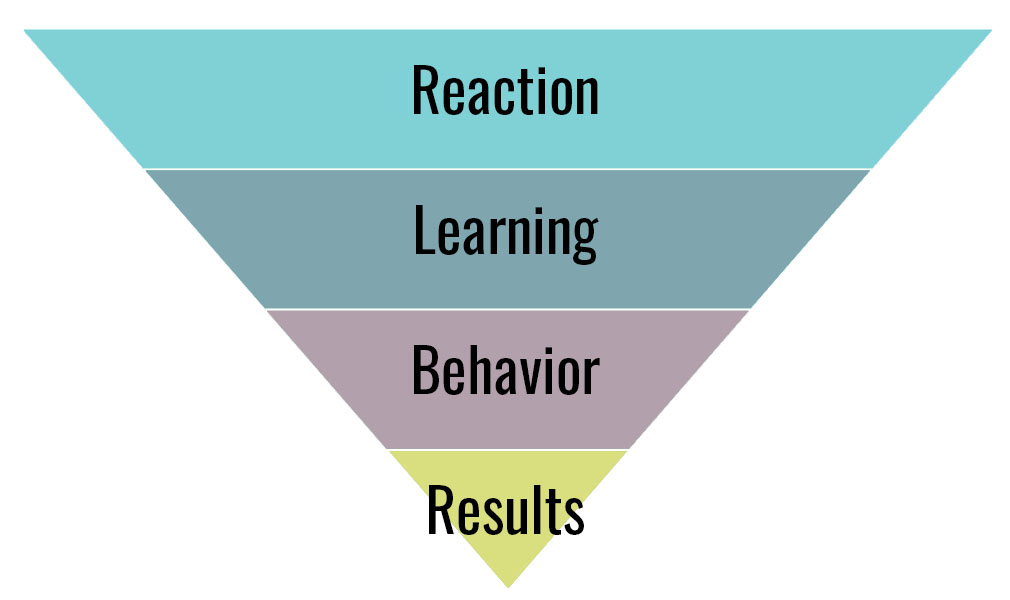

There are several evaluation frameworks available for training development. One of the more common and practically useful frameworks is the Kirkpatrick Four Levels of Training Evaluation. Figure 6 provides a visual representation of the framework with the most basic form of evaluation at the top (reaction) and the most sophisticated form of evaluation at the bottom (results).

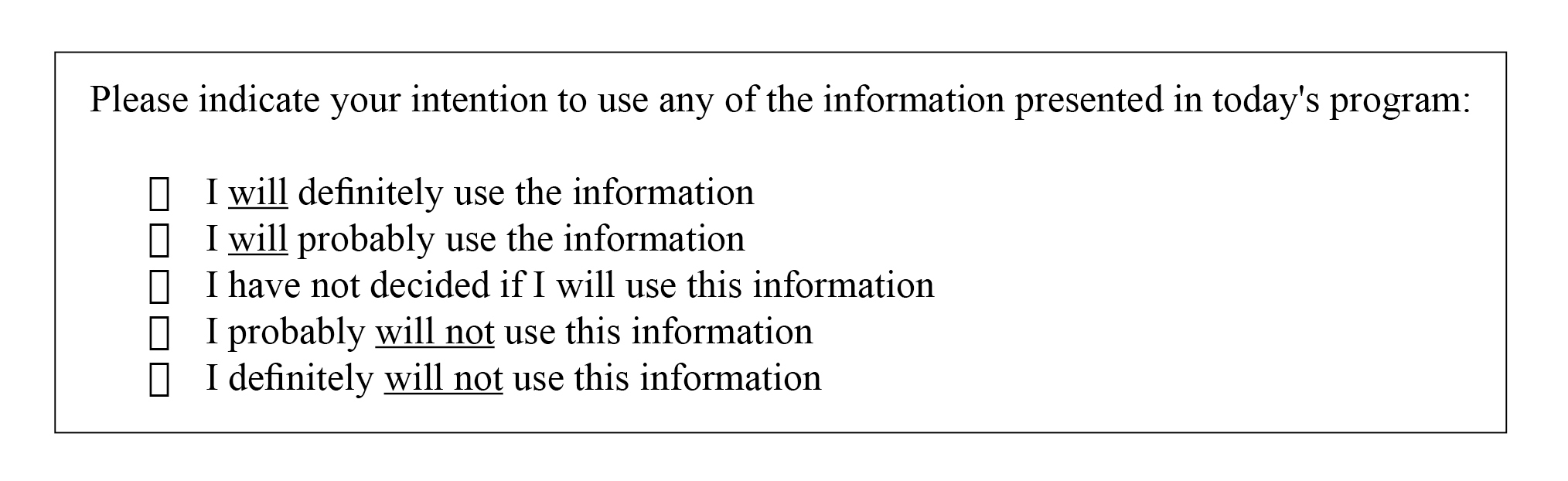

Each one of these levels is focused on specific aspects of the training.

- Reaction—Did you like the training?

- Learning—Did you learn something?

- Behavior—Do you intend to use the training?

- Results—What is the impact of the training?

There are many different approaches and tools that have been developed to help gather and report information across the different levels. Consider using The Public Value of Extension tool (https://open.clemson.edu/joe/vol58/iss6/6/), which has been designed to help capture and quantify learning, behavior, and results.

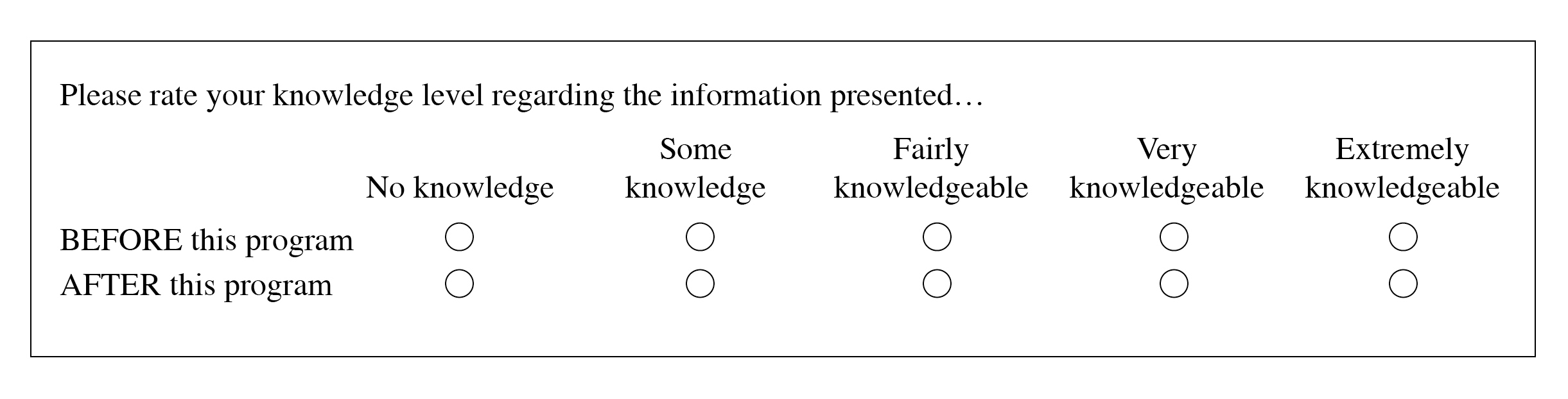

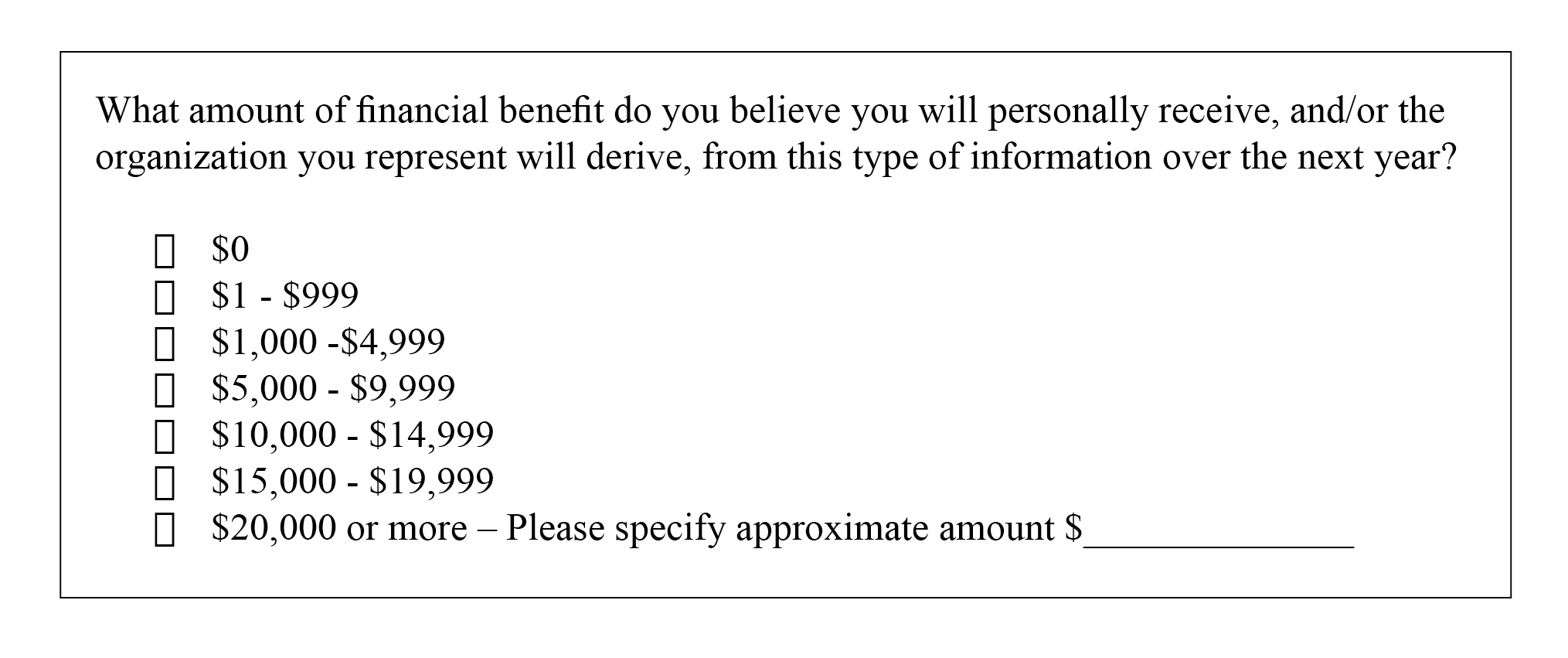

A very brief summary of the type of data collected for each level is included in Figures 7–9 below.

This learning-related question is likely a critical data point for you as you consider why only 5% of the cotton growers have adopted the new BMPs. You may anticipate that they had little knowledge of the topic before this program, indicating that they had not been presented with the information. You expect that as a result of participating in your training, they will experience a knowledge increase. This data point will quantitatively give you an answer.

Behavior change is what we strive for as Extension professionals. We want to provide our stakeholders with the information and skills to improve their lives. The new BMPs have shown evidence of increased yields with reduced fertilizer and pesticide use—an increase in income with a reduction in input costs. This data point can help you understand if they intend to implement the BMPs or not.

5.3 Results

If behavior change is what we strive for, results are the ribbon on top. As stated above, results can be thought of as the impact your training will have on the participants. You will obviously want to alter the question and response options to fit your training. For example, if a training is about a health practice or leadership topic, the results question and responses may look very different from what is shown here.

In evaluating the cotton BMP training, perhaps the Extension team used surveys to track whether growers planned to adopt the recommended techniques in the next planting season. Six months later, they followed up to see if fertilizer costs had decreased and yields had increased. This data provided tangible evidence of the training’s impact, aligning with the Kirkpatrick “Behavior” and “Results” levels and offering proof of the practical value of the best management practices.

5.4. Wrapping Up

Collecting evaluation data on your training program is important to quantify the value of the program and help improve the program in the future. A few highlights:

- Collecting evaluation data on your training is important for recordkeeping and practical reasons.

- The Kirkpatrick Four Levels of Training model is useful for capturing a range of evaluation data—reaction, learning, behavior, and results.

- The Public Value of Extension tool can serve as a quick and efficient way to gather evaluation feedback for your training.

Equipped with evaluation results, you can refine your training, demonstrate its value, and improve future programs. When we use all five ADDIE phases together, this structured approach can help support high-impact online learning.

Summary

Creating online learning can be a very effective way to share information with our stakeholders. As Extension professionals we may find ourselves in a situation where we have important information, but it is simply not reaching learners. By applying each ADDIE step to our cotton BMP example—assessing grower needs, designing relevant objectives, developing appropriate content, implementing a targeted launch, and evaluating real-world impact—we can see this approach to online training can lead to higher adoption rates and, ultimately, more profitable and sustainable cotton production.

Using the ADDIE framework, we can pragmatically work through the training development process and ensure the training we create is rigorous and beneficial. As a reminder:

- assess: 5%–15% of the project.

- design: 15%–25% of the project.

- develop: 30%–50% of the project.

- implement: 5%–20% of the project.

- evaluate: 5%–15% of the project.

Appendix 1. Quick Reference Guide: The ADDIE Model for Extension Online Training.

| Phase | Time allocation | Key tasks | Typical deliverables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assess (Analyze) | 5%–15% | Identify training goals Define target audience Determine resources & constraints Conduct needs assessments | Clear statement of training goal Audience profile Resource inventory Needs assessment summary |

| Design | 15%–25% | Draft learning objectives (TLOs/ELOs) Select instructional strategies Plan content flow & structure Map objectives to Bloom’s levels | Course blueprint or outline Draft objectives Activity plan or storyboard |

| Develop | 30%–50% | Gather & create content (videos, readings, quizzes) Integrate materials in chosen platform Run pilot tests Refine based on feedback | Completed course modules Media assets (videos, PDFs, images) Pilot test feedback & revisions |

| Implement | 5%–20% | Prepare platform for launch Market & promote to intended audience Launch course (soft or full) Monitor initial participation | Live/accessible online course Implementation plan Engagement metrics |

| Evaluate | 5%–15% | Collect feedback (reaction & learning) Track behavior changes & results Use Kirkpatrick or similar model Report & use insights to improve | Evaluation data Outcomes/impact report Revised or follow-up training plan |

How to Use This Guide

- Plan the timeline: Estimate the total resources and time you have, then use the suggested percentages to allocate effort across the five phases.

- Coordinate the team: Assign responsibilities for each phase—e.g., needs assessment experts for “Assess,” content creators for “Develop,” etc.

- Track deliverables: Use the “Typical Deliverables” column as milestones to ensure progress.

- Iterate & improve: Remember that ADDIE is cyclical. Your evaluation phase might yield findings that prompt a fresh round of assessment or design adjustments.

References

Allen, M. W. (2016). Michael Allen’s guide to e-learning: Building interactive, fun, and effective learning programs for any company. Wiley Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119176268

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1: cognitive domain. David McKay Company, Inc. https://eclass.uoa.gr/modules/document/file.php/PPP242/Benjamin%20S.%20Bloom%20-%20Taxonomy%20of%20Educational%20Objectives%2C%20Handbook%201_%20Cognitive%20Domain-Addison%20Wesley%20Publishing%20Company%20%281956%29.pdf

Branson, R. K., Rayner, G. T., Cox, J. L., Furman, J. P., King, F. J., & Hannum, W. H. (1975). Interservice procedures for instructional systems development (TRADOC Pam 350-30, NAVEDTRA 106A). U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA019486.pdf

Borich, G. D. (1980). A needs assessment model for conducting follow-up studies. The Journal of Teacher Education, 31(3), 39–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248718003100310

Caffarella, R. S., & Daffron, S. R. (2013). Planning programs for adult learners: A practical guide. Jossey-Bass.

Dick, W., Carey, L., & Carey, J. O. (2015). The systematic design of instruction (8th ed.). Pearson.

Garrison, D. R., & Anderson, T. (2003). E-learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203166093

Garrison, D. R., & Vaughan, N. D. (2013). Blended learning in higher education: Framework, principles, and guidelines. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118269558

Kirkpatrick, D. J., & Kirkpatrick, W. K. (2016). Kirkpatrick’s four levels of training evaluation. Association for Talent Development.

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2015). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development (8th ed.). Routledge.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

Lamm, A. J., Rabinowitz, A., Lamm, K. W., & Faulk, K. (2020). Measuring the aggregated public value of extension. The Journal of Extension, 58(6), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.34068/joe.58.06.06

Merrill, M. D. (2002). First principles of instruction. Educational Technology Research and Development, 50(3), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02505024

Morrison, G. R., Ross, S. M., Morrison, J. R., & Kalman, H. K. (2019). Designing effective instruction (8th ed.). Wiley.

Norton, G. W., & Alwang, J. (2020). Changes in agricultural extension and implication for farmer adoption of new practices. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 42(1), 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13008

Peterson, C. (2003). Bringing ADDIE to life: Instructional design at its best. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 12(3), 227–241. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/2074/

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

Smith, P. L., & Ragan, T. J. (2004). Instructional design (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Vaughan, N. D. (2010). A blended community of inquiry approach: Linking student engagement and course redesign. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(1–2), 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.007

West, R. E., & Borup, J. (2014). An analysis of a decade of research in 10 instructional design and technology journals. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(4), 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12081

Whittington, S. M., Rudd, R., Elliot, J., Drape, T., Faulkner, P. Greenhaw, L. L., Jagger, C., Mars, M., Marsh, M., Marsh, M., McCubbins, O. P., McKim, A. J., Odom, S., Redwine, T., Rice, A. H., Rubenstein, E., Scherer, H. H., Smith, K. L., Specht, A., … & Westfall-Rudd, D. (2023). The art and science of teaching agriculture: Four keys to dynamic learning. Virginia Tech Publishing. https://doi.org/10.21061/teachagriculture

Yuan, J., & Kim, C. (2014). Guidelines for facilitating the development of learning communities in online courses. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 30(3), 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12042