Carpenter bees (Figure 1) can be a serious pest on outdoor structures made of wood, such as patios, decks, siding of homes, sheds, furniture, etc. The large carpenter bee, Xylocopa virginica, is the most common species found in Georgia. Adult carpenter bees are pollinators, but mated females bore tunnels into wooden structures to raise their larvae. This process can cause substantial damage to the wood, even sometimes compromising the integrity of wooden structures.

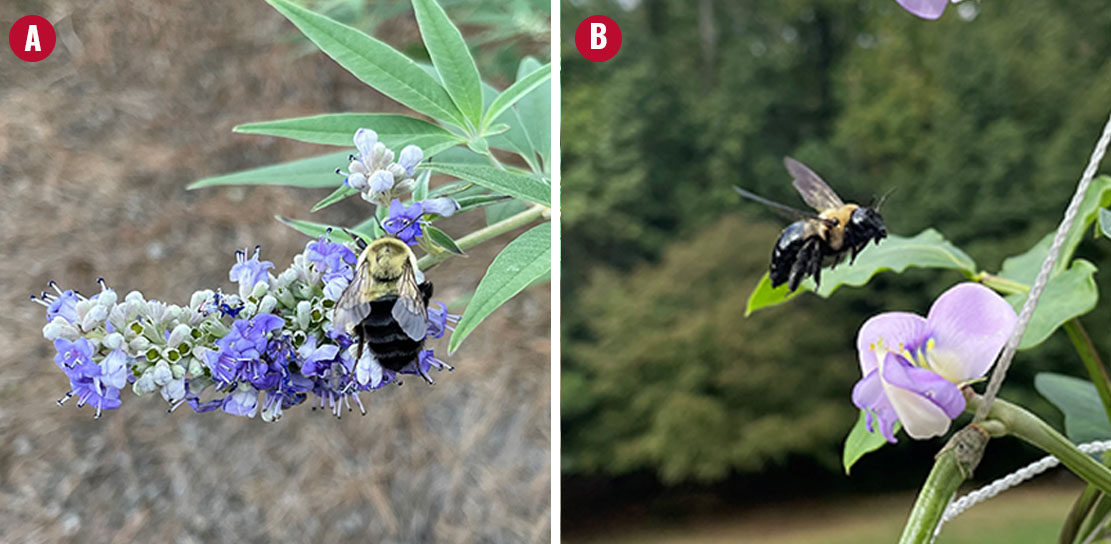

Carpenter bees are more attracted to redwood, cedar, cypress, and pine, especially when old and unpainted. The body of a carpenter bee is metallic black with a glossy and hairless abdomen (Figure 1).

Bumblebees look similar to carpenter bees, but the abdomens of bumblebees are hairy with yellow and black stripes (Figure 2A). Also unlike carpenter bees, bumblebees do not use wooden structures to build their nests. Instead, they use abandoned rodent burrows in the ground. It’s important to distinguish between the two, as carpenter bees present unique threats that require specific preventative measures.

Biology and Lifecycle

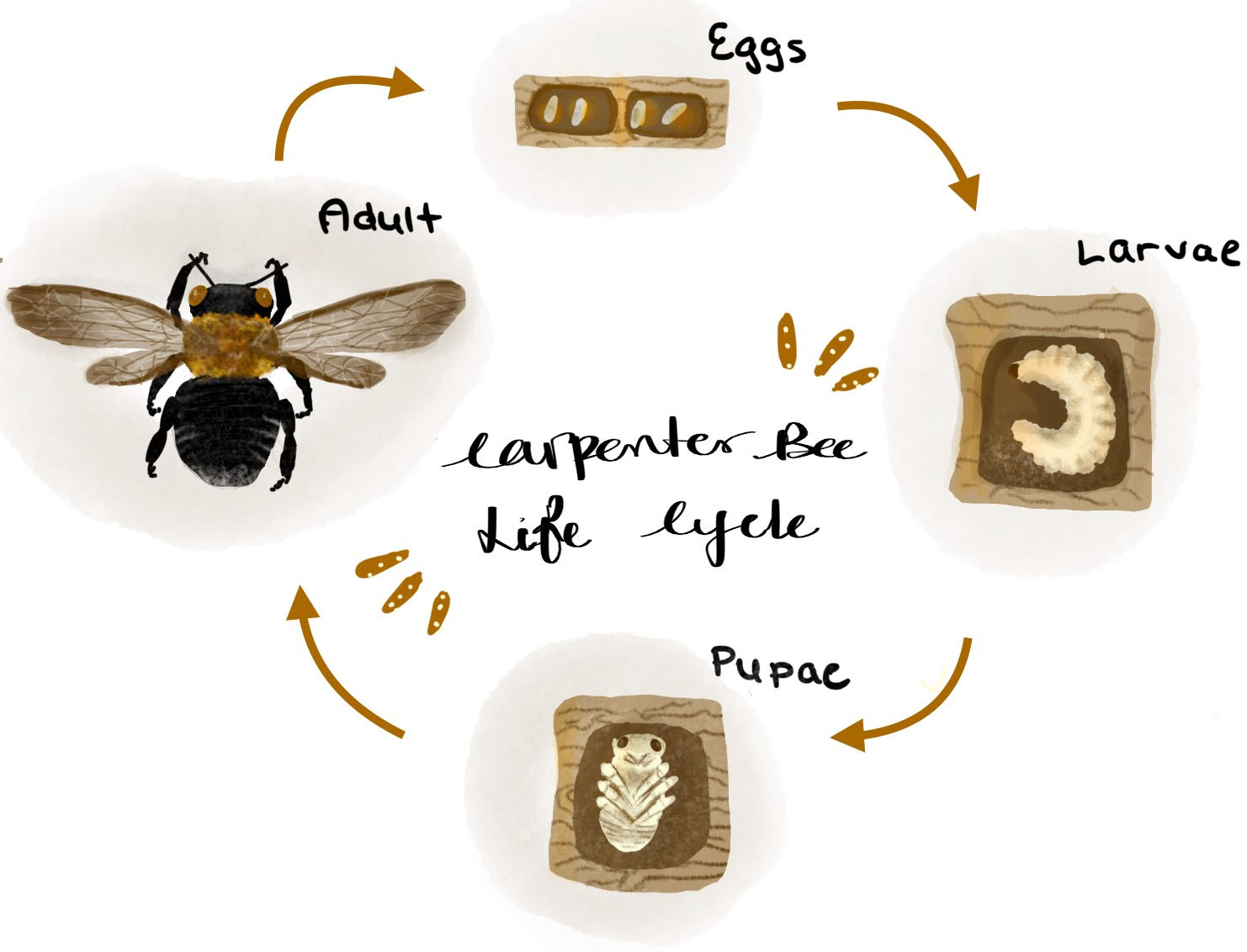

The life stages of carpenter bees are egg, larva, pupa, and adult (Figure 3). Unlike bumblebees and honeybees, which are social, carpenter bees are not social insects. Carpenter bees do not live in colonies with workers, drones, and queens. They are solitary, meaning one adult is in each nest, and eggs or larvae develop inside the nest. Adult carpenter bees singly overwinter from November to February.

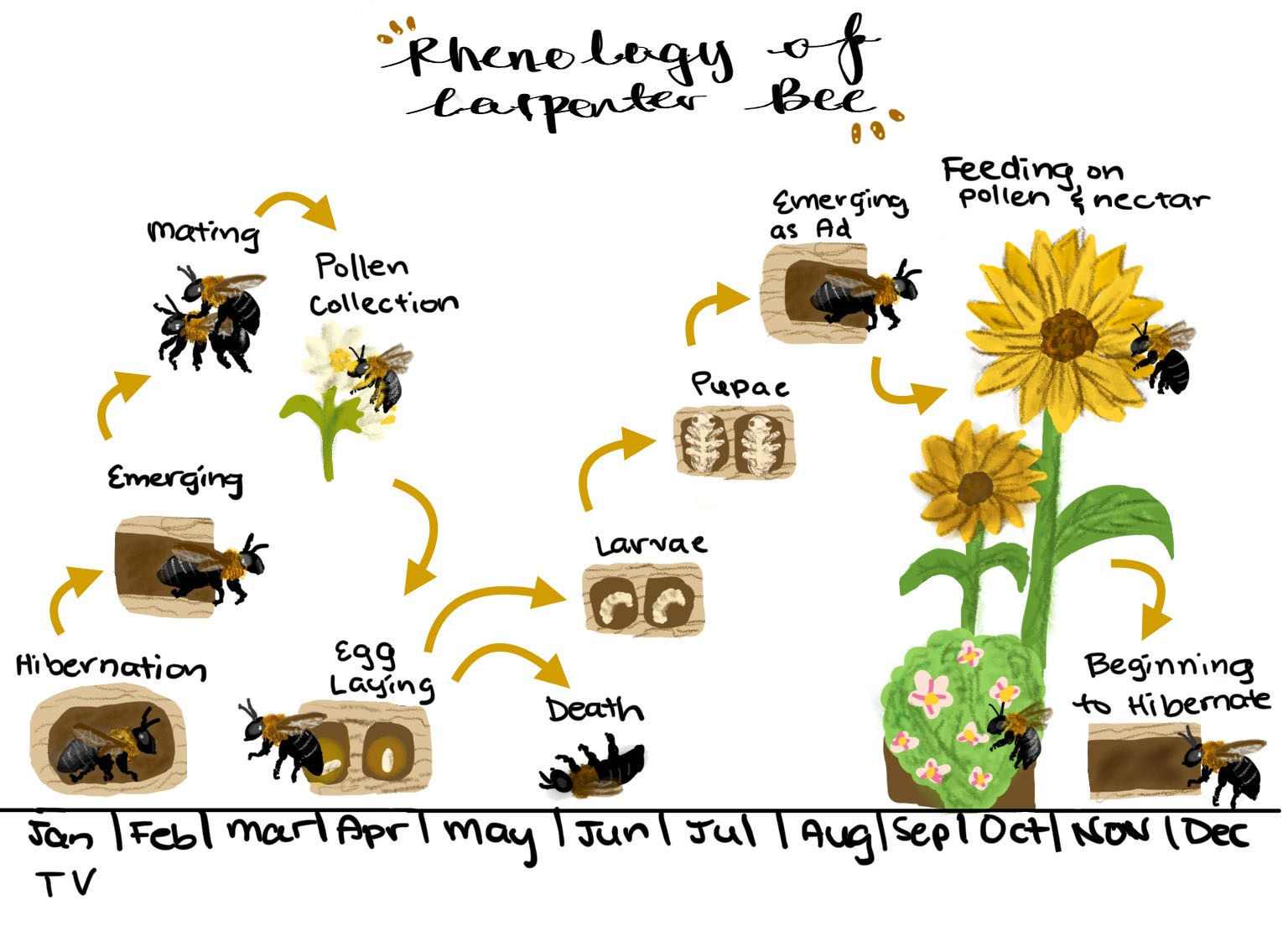

An adult carpenter bee moves into existing tunnels that their parents bore in the spring and summer for overwintering (Figure 4). Females and males emerge from their tunnels in February and mate. Mated females then bore tunnels into wood (Figure 5).

From March to April, once the brood tunnel is completely drilled, females singly lay eggs in compartments or cells. The depth of the tunnels varies. During egg laying, females forage pollen and nectar from the immediate landscape to provision food (as a ball) in each cell near those eggs. Once an egg is laid and provisioned, the bee builds a wall using wood pulp and regurgitates it to form a cell.

Adults also feed on pollen for their energy needs. Males guard the nests to prevent multiple females from entering them and using the tunnels to lay eggs. Once the egg-laying is completed, the females die off.

Eggs hatch in March–April, and larvae gradually grow by molting from one stage to another, feeding on the food ball prepared within each cell. They pupate inside the cells, and by August, new adults emerge from those tunnels (Figure 5).

These new adults move out of nests to forage and feed on pollen and nectar from various floral resources from the late summer to fall, developing their nutrient reserves to survive the winter. As temperatures decrease in the fall (in November), those new adults move into preexisting brood tunnels. They overwinter in those tunnels and then emerge in February of the following year to continue the cycle.

Damage Caused by Carpenter Bees

Female carpenter bees bore into the wood, leaving round-shaped entry holes about 1 cm (0.39 in.) in diameter (Figure 6A). As they bore, they push out sawdust near the entry hole (Figure 6B) — they do not feed on the wood.

The boring activity produces sounds that can be heard coming from the wood. Although they make perfect entry holes, they bore along the length of the wood after a short perpendicular hole. Females sometimes reuse existing tunnels. Repeated tunneling on the same wood for many years can compromise a structure’s integrity.

Although carpenter bees fly around aggressively during mating, constructing, or guarding their nests, they rarely attack humans or animals. This is especially true for males, who do not have stingers. People should be aware that woodpeckers are one of the important predators of carpenter bees; woodpeckers are especially attracted to the bees while they are actively boring the wood, as this process produces a unique sound. Woodpeckers can break the structures that the carpenter bees are boring into and cause structural damage as they try to access the adult females and larvae developing in the tunnels (Figure 7).

Management of Carpenter Bees in the Landscape

Carpenter Bee Traps

Installing traps close to carpenter bee activity—such as near patios, porches, decks, sheds, barns, or houses—can reduce their population. Many traps are available (Figure 8) and can be purchased from local garden stores or online.

Female carpenter bees naturally explore existing entry holes, and this behavior is utilized in the design of most traps (Figure 8A). Once they enter holes in these traps, females are trapped in a plastic bottle or box with restricted passage to return; they do not bore through plastic, metal, or glass material. The trapped carpenter bees die within the collection container. Sticky traps can also effectively capture carpenter bees (Figure 8B); however, they will have bycatch, or unintentional catches, such as paper wasps, etc.

Physical Control

Carpenter bees can be physically removed by using netting or swatting with a flat bat. If this approach is followed through consistently, some adults could be eliminated.

Plugging Entry Holes

Searching for and plugging entry holes on wooden structures may reduce the repeated use of the same nests by carpenter bees. These can be plugged by hammering wooden dowels into the holes and coating them with sealants such as glue or putty. Females inside the nest will not bore an exit hole if they are trapped by the plugs. Severely damaged wood may need to be replaced, especially if the wood that supports a structure is seriously damaged.

Cultural Control

Although the effects of paint and staining are poorly understood, anecdotal observations indicate that carpenter bees avoid wood painted with oil-based paint for building nests. Bringing inside some wooden structures, such as pieces of furniture, can reduce the damage from boring bees. Keep outside doors shut, especially in the early spring, to reduce access to wooden structures.

Chemical Control

Insecticides can be used to prevent the completion of nest construction. Pyrethroid insecticides are effective and can be sprayed directly into the entry hole. Dust formulations of insecticides are also effective in reducing carpenter bee problems.

Once an insecticide is applied, bees will spread its residue inside the tunnels as they move in and out. Leaving the tunnel open for a couple of days after the insecticide application will increase the effectiveness of the applied insecticide. After 1 or 2 days, the holes can be plugged. The residual activity of pyrethroid insecticides will not last more than 4 weeks, so repeated application might be necessary in some cases.

If high activity of carpenter bees is anticipated in an area, these insecticides could be sprayed on the structure before females begin their boring activity in the spring. Again, the insecticide residue on the surface will lose efficacy within a few weeks, and reapplication will be needed. The downside of this approach is that it is challenging to get good insecticide coverage on the entire surface of vulnerable structures, especially if they are large, such as decks or homes.

Wear proper personal protection equipment (PPE), such as gloves, long-sleeved shirts, etc., as recommended on insecticide labels. Pay attention to the direction of the wind to prevent exposure. Because carpenter bee damage could be in areas of wooden structures typically out of sight and not reachable, seek appropriate support. For professional applications, pest control companies are equipped to reach damaged areas of the structure.

References

Balduf, W. V. (1962). Life of the carpenter bee, Xylocopa virginica (Linn.) (Xylocopidae, Hymenoptera). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 55(3), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/55.3.263

Hurd, P. D., Jr. (1958). Observations on the nesting habits of some new world carpenter bees with remarks on their importance in the problem of species formation (Hymenoptera: Apoidea). Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 51(4), 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/51.4.365

Jones, S. C. (2017). Carpenter bees (Publication No. HYG-2074). Ohio State University Extension. https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/hyg-2074

Potter, M. F. (2018). Carpenter bees (Publication No. Entfact-611). University of Kentucky Cooperative Extension. https://entomology.ca.uky.edu/ef611

Sabrosky, C. W. (1962). Mating in Xylocopa virginica. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington, 64, 184. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/16339303