Takeaways

- 30% to 40% of contaminants in our homes are tracked in from outside.

- These contaminants can aggravate allergies and asthma.

- Removing your shoes upon entry and using a good doormat can help reduce contaminants inside your home.

What’s in the Dust in Your Home?

Household dust is made up of a variety of items, including insect fragments, lead dust, pesticides, pollen, dust mites, animal dander, hair, human skin flakes, fungal spores, or cigarette ash, and and even polyfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS (Moschet, et al., 2018; Savvaides, et al., 2021).

Around 30% to 40% of the contaminants inside your home are brought in from outdoors, and studies indicate that the cockroach exoskeletons and droppings found in household dust can trigger asthma (Ferguson & Kim, 1991).

Dust gets into your home on shoes and clothing, or pets can track contaminants in on their paws and fur (Rashid et al., 2016). Not surprisingly, the greatest concentration of household dust is found in carpeting near the entryway.

Children are at greatest risk of exposure to contaminants found in household dust. This is because they are more likely to be sitting and crawling on floors and placing their hands in their mouths. Numerous studies confirm that the greatest number of environmental exposures and risks, especially for young children, occur inside the home (Roberts et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2025). Children are not the only ones at risk. Anyone with asthma, other respiratory problems, or a weakened immune system should make every effort to reduce household dust.

What You Can Do to Reduce Contaminants Indoors

Every step you take inside your home brings in the debris and contaminants that are on your shoes and clothing. By taking a few simple steps, you can improve the health of your home and reduce the time spent cleaning.

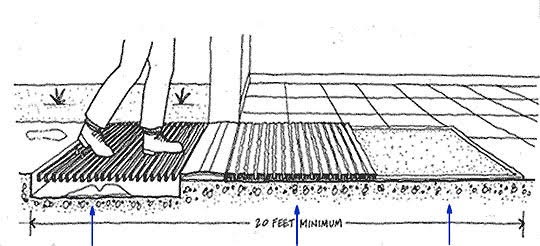

- Establish an entry system that captures soil, pollutants, and moisture at the door. Your entry system should consist of a hard-surfaced walkway, such as a paved sidewalk, a grate-like scraper mat outside the entry door, and a highly absorbent doormat that will trap soil and water below shoe level placed just inside the door.

- If you have space, add a second doormat as a finishing mat. The purpose of this mat is to capture and hold any remaining particles or moisture from the bottom of your shoes.

- Remove your shoes and leave them at the door. The carpet inside your home acts like a doormat, scraping off debris and dirt with every step you take. Removing your shoes at the door not only leaves contaminants behind, it reduces wear and tear on your floors and time spent cleaning. To prevent slips and falls indoors, choose an indoor shoe, slipper, or sock with a nonslip sole. If you have balance issues or a tendency to bump into things, choose a hard-soled shoe with good traction to wear indoors.

A Clean Doormat is a Good Doormat

Doormats help reduce tracking in contaminants. Leaving contaminants and shoes at the door has time, economic, and health benefits.

Adding a doormat reduces the time and effort needed to clean your home. You will save money by reducing wear and tear on your carpets and floors. The health benefits come from reducing your exposure to pesticides, lead dust, and contaminants that may trigger allergies or asthma.

Key Features of a Good Doormat

- stores soil and water below shoe level

- has a nonslip backing

- made with a reinforced surface to avoid wearing out quickly

Project: Create a Shoe Storage Unit

- Keep outside shoes out of the way.

- Store inside shoes near the door.

- Provide guests with slippers to wear inside.

References

Ferguson, J. E., & Kim, N. D. (1991). Trace elements in street and house dust: Sources and speciation. Science of the Total Environment, 100, 125–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-9697(91)90376-P

Moschet, C., Anumol, T., Lew, B. M., Bennett, D. H., & Young, T. M. (2018). Household dust as a repository of chemical accumulation: New insights from a comprehensive high-resolution mass spectrometric study. Environmental Science & Technology, 52(5), 2878–2887. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b05767

Oh, J., Buckley, J. P., Kannan, K., Pellizzari, E., Miller, R. L., Bastain, T. M., Dunlop, A. L., Douglas, C., Gilliland, F. D., Herbstman, J. B., Karr, C., Porucznik, C. A., Hertz-Picciotto, I., Morello-Frosch, R., Sathyanarayana, S., Schmidt, R. J., Woodruff, T. J., Bennett, D. H., & the ECHO Cohort Consortium. (2025). Exposures to contemporary and emerging chemicals among children aged 2-4 years in the United States: Environmental influences on the Child Health Outcome (ECHO) Cohort. Environmental Science and Technology, 59(27), 13594–13610. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.4c13605

Rashid, T., VonVille, H. M., Hasan, I., & Garey, K. W. (2016). Shoe soles as a potential vector for pathogen transmission: a systematic review. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 121(5), 1223–1231. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.13250

Roberts, J. W., Wallace, L. A., Camann, D. E., Dickey, P., Gilbert, S. G., Lewis, R. G., & Takaro, T. K. (2009). Monitoring and reducing exposure of infants to pollutants in house dust. In D. Whitacre (Ed.), Reviews of environmental contamination and toxicology (Vol. 201, pp. 1–39). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0032-6_1

Roberts, J. W., & Ott, W. R. (2006). Exposure to pollutants from house dust. In W. R. Ott, A. C. Steinemann, & L. A. Wallace (Eds.), Exposure analysis (pp. 319–345). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420012637

Savvaides, T., Koelmel, J. P., Zhou, Y., Lin, E. Z., Stelben, P., Aristizabal-Henao, J. J., Bowden, J. A., & Pollitt, K. J. G. (2021). Prevalence and implications of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in settled dust. Current Environmental Health Reports, 8, 323–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-021-00326-4

Revised from the original 2010 publication written by Pamela R. Turner, Sharon M.S. Gibson, and Ambre Latrice Reed, which was updated in 2015 by Dr. Turner.

For more information on healthy homes, visit healthyhomes.uga.edu.