Introduction

The silverleaf whitefly (SLWF), Bemisia tabaci Gennadius (also referred to as sweet potato whitefly), is a major insect pest of cucurbit vegetable crops in southern Georgia. Whiteflies damage cucurbits mainly by causing silverleaf disorder and transmitting viruses.

Effective and sustainable management of whiteflies and whitefly-transmitted viruses (WTVs) requires an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy. A primary component of IPM is selecting crops that are the most resistant or tolerant to a particular pest or disease. Selecting appropriate cucurbit species, crops, and cultivars is crucial to minimize yield losses caused by whiteflies and the viruses they transmit. This resource describes whiteflies and the damage they cause in cucurbit crops and offer recommendations for crops that are resistant or tolerant to silverleaf disorder and WTVs for fall-season production in southern Georgia.

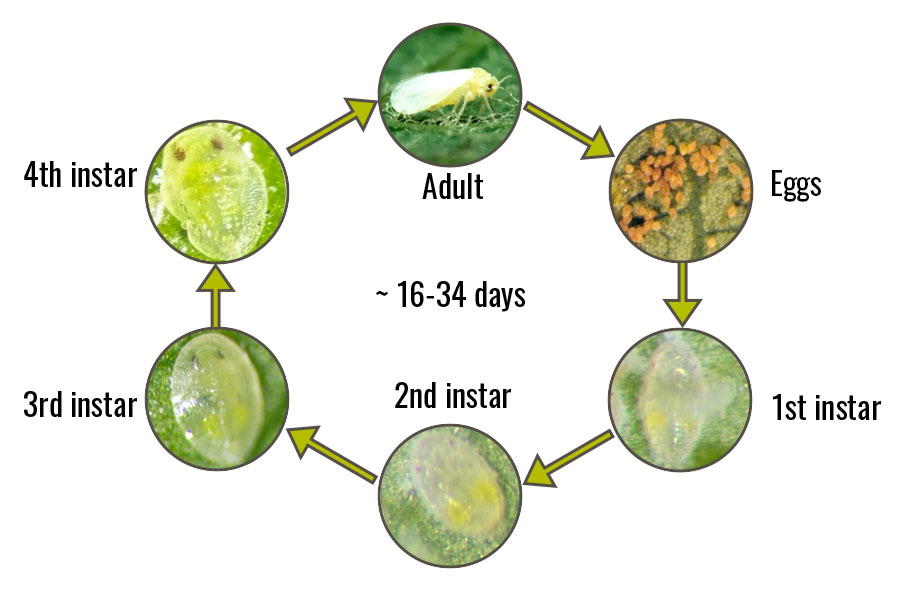

Adult: Photo: Scott Bauer, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org.

Egg: Photo: David Riley, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org.

Instars: Photos: Nirmala Acharya.

Whitefly Life Cycle and Biology

The silverleaf whitefly life cycle consists of eggs, four nymphal instars, and adults, and spans 16–34 days, depending on temperature (Figure 1). Females lay 50–400 pointed, oblong yellow eggs on the underside surfaces of leaves (Riley & Roberts, 2020), which darken to brown when mature and hatch in 4–12 days. The first-instar nymphs (crawlers) emerge with six functional legs and antennae. Crawlers find feeding sites in leaves and insert their mouthparts to suck phloem sap. Then they molt into legless, flattened second instars. These molt into dome-shaped third instars, followed by fourth instars. The fourth nymphal stage is characterized by distinct red eyes. Late fourth-instar nymphs transition into adults by shedding their exoskeletons (Barman et al., 2020).

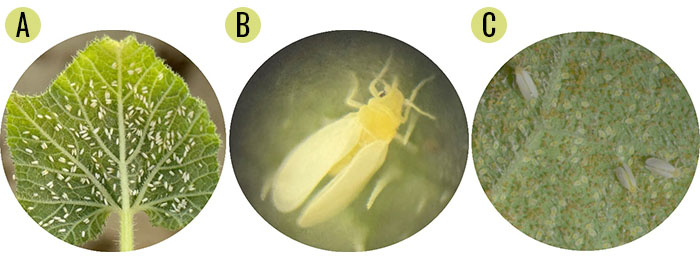

The adult insect is small—less than 2 mm in body length and about 2 mm in wing expanse—with piercing and sucking mouthparts (Figure 2). Immature and adult silverleaf whiteflies feed on phloem sap from the bottom surface of leaves (Arshad et al., 2023).

Photos: Nirmala Acharya.

Damage Caused by Silverleaf Whitefly

Silverleaf whiteflies have a broad host range, feeding on crops and weeds of several plant families, including Cucurbitaceae, Solanaceae, Leguminosae, Malvaceae, and Brassicaceae. The diverse cropping systems in southern Georgia make it an ideal location for whitefly populations to build up, creating severe crop infestations. Because whiteflies can overwinter in cole crops (kale, collards, cabbage, etc.) grown during the winter months, they easily move to spring cucurbits, followed by summer-grown cotton. Subsequently, they migrate to fall-grown vegetable crops such as cucurbits, tomatoes, and snap beans, where they can damage plants and significantly reduce yields through direct and indirect mechanisms (Sparks et al., 2018).

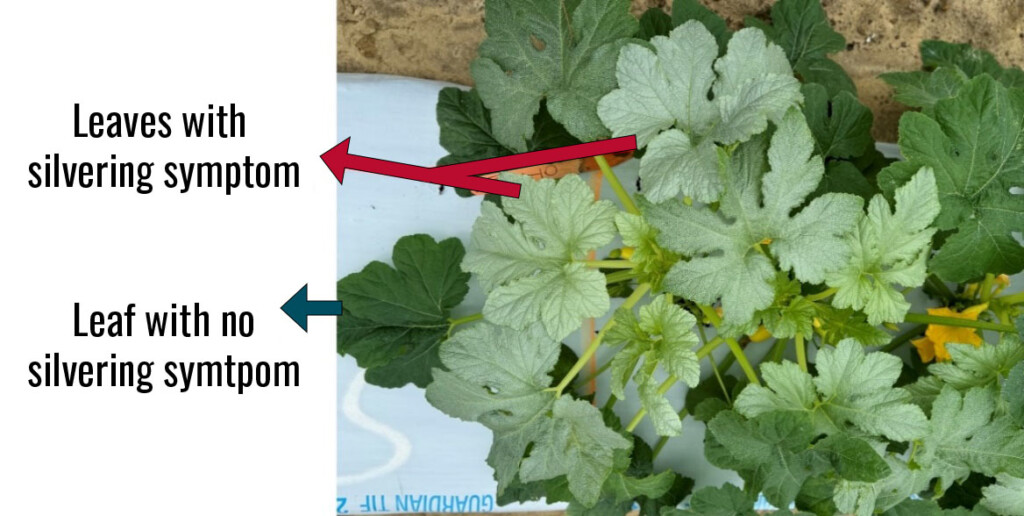

Direct damage involves feeding on phloem sap, which may cause silverleaf disorder in cucurbits, as well as stunted plant growth, low photosynthetic efficiency, and fruit deformities. Silverleaf disorder is caused by the immature whiteflies feeding on phloem sap and creating air pockets by separating the upper epidermis (top layer of cells) from the palisade mesophyll cells (the layer underneath the upper epidermis that is the main area of photosynthetic activity), which alters light reflection, giving cucurbit leaves a silvery appearance (Figure 3).

Photo: Nirmala Acharya.

Indirect damage involves the excretion of honeydew during feeding, which enhances the development of sooty mold fungus and, more importantly, the transmission of several viruses (Dutta et al., 2024). Table 1 provides details on common whitefly-transmitted viruses in southern Georgia. Cucurbit leaf crumple virus (CuLCrV), cucurbit yellow stunting disorder virus (CYSDV), and cucurbit chlorotic yellows virus (CCYV) all infect crops as both single and mixed infections (Devendran et al., 2023). These viruses are excreted in salivary fluids during feeding.

| Viruses | Species | Genus | Group | Host |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cucurbit Leaf Crumple Virus (CuLCrV) | Begomovirus cucurbitae | Begomovirus | DNA | Cucurbits and snap beans |

| Cucurbit Chlorotic Yellows Virus (CCYV) | – | Crinivirus | RNA | Cucurbits |

| Cucurbit Yellow Stunting Disorder Virus (CYSDV) | Crinivirus cucurbitae | Crinivirus | RNA | Cucurbits |

Symptoms of Whitefly-Transmitted Viruses in Cucurbits

Virus symptoms can vary among cucurbit species and crops (Table 2). Generally, CuLCrV symptoms begin with diffuse yellow spots in new leaves and progress to crumpling, curling of leaves, thickening of veins, and plant stunting in severe cases.

Similarly, the symptoms of CYSDV initially appear as a yellow-green chlorotic mottle in older leaves, which develops into interveinal chlorosis, yellowing, and stunting of plants in intense cases. CCYV symptoms are indistinguishable from the CYSDV symptoms. The CCYV symptoms begin as chlorotic spots with diffuse margins in older leaves, which later merge and develop into interveinal chlorosis, and leaves have a brittle appearance. New leaves in infected plants show chlorosis and yellowing between the veins. However, growers should keep in mind that mixed infections of CuLCrV, CYSDV, and CCYV are common (Devendran et al., 2023).

| Crop | Symptom Severity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silverleaf Disorder | CuLCrV | CYSDV | CCYV | |

| Short-season | ||||

| Cucumber Cucumis sativus | resistant | resistant | low to moderate | low to moderate |

| Summer squash | ||||

| Zucchini Cucurbita pepo | low to high | low to high | low to high | low to high |

| Yellow squashCucurbita pepo | moderate to high | moderate to high | moderate to high | moderate to high |

| Long-season | ||||

| Winter squash | ||||

| Butternut Cucurbita moschata | resistant to moderate | low | low to moderate | low to moderate |

| Calabaza Cucurbita moschata | resistant to low | low | low to moderate | low to moderate |

| Kabocha Cucurbita maxima | high | moderate | moderate to high | moderate to high |

| Acorn Cucurbita pepo | moderate to high | high | high | high |

| Hubbard Cucurbita maxima | high | moderate | moderate to high | moderate to high |

| Other cucurbits | ||||

| Pumpkin Cucurbita pepo; Cucurbita maxima | moderate to high | moderate to high | high | high |

| Watermelon Citrullus lanatus | resistant | high | high | high |

Crop-Specific Details on Silverleaf Disorder and Virus Severity

Short-Season Crops

Yellow Squash

In yellow squash, the severity of silverleaf disorder (Figure 4A) and symptoms of WTVs vary among cultivars, ranging from moderate to high. Mixed infections of CuLCrV, CYSDV, and CCYV show more pronounced symptoms than single-virus infections.

Infection with CuLCrV alone results in crumpling, curling of leaves, thickening of veins, and, in severe cases, plant stunting (Figure 4B), while a mixed infection of CuLCrV, CYSDV, and CCYV leads to crumpling, curling, chlorosis, yellowing of leaves, and stunting of the plant (Figure 4C). Virus-infested yellow squash fruits exhibit green streak markings. Overall, yellow squash is the most negatively impacted short-season cucurbit crop by silvering and WTVs.

Photos: Nirmala Acharya.

Zucchini

In zucchini, the intensity of silverleaf disorder (Figure 5A) and symptoms caused by WTVs infestation vary among cultivars, ranging from low to high. Mixed infections of CuLCrV, CYSDV, and CCYV exhibit more severe symptoms than single infections. A single infection with CuLCrV causes mild chlorosis, crumpling, curling of newer leaves, and thickening of veins (Figure 5B), while a mixed infection of CuLCrV, CYSDV, and CCYV results in chlorosis, crumpling, curling, yellowing of leaves, and stunting of the plant (Figure 5C).

Virus symptoms that render fruits unmarketable are less common in zucchini fruits than in yellow squash. Therefore, we recommend planting zucchini squash over yellow squash because of its moderate silvering and moderate WTV damage potential.

Photos: Nirmala Acharya.

Cucumber

Unlike squash, cucumber leaves do not show visible symptoms of silvering disorder (Figure 6A). Cucumbers are also resistant to curling and crumpling symptoms caused by CuLCrV. However, chlorosis and yellowing because of CYSDV, and CCYV single- and mixed-infection symptoms are common in cucumbers (Figure 6B). Depending on the cultivar, the severity of CYSDV and CCYV symptoms varies from low to moderate. Cucumber fruits do not exhibit WTV symptoms that would make them unmarketable. We recommend growing cucumber as the best short-season cucurbit crop in the fall because of its resistance to silvering and CuLCrV.

Photos: Nirmala Acharya.

Long-Season Crops

Winter Squash

Silverleaf disorder and virus symptoms vary from low to severe depending on the species and types of winter squash. The variation in severity of silverleaf disorder among winter squash types is shown in Figure 7. Silverleaf disorder and virus symptoms in winter squash species and types are described below.

Photo: Nirmala Acharya.

Acorn (Cucurbita pepo)

The severity of silverleaf disorder among the winter squash species and types is comparatively lower in acorn squash (Cucurbita pepo; Figure 8A) compared to Cucurbita maxima (kabocha and hubbard) but is higher than found in butternut (Cucurbita moschata). In contrast, acorn squash exhibits severe curling and crumpling symptoms from CuLCrV. Acorns are highly susceptible to CYSDV and CCYV.

Like zucchini and yellow squash, infection with CuLCrV alone results in crumpling and curling of newer leaves, thickening of veins, and plant stunting in extreme cases (Figure 8B), while a mixed infection of CuLCrV, CYSDV, and CCYV leads to chlorosis, curling, crumpling, yellowing of leaves, and stunting of the plant (Figure 8C).

Acorn fruits are prone to displaying virus symptoms, rendering them unmarketable. Overall, acorn squash is one of the most negatively impacted long-season cucurbit crops because of silvering and WTVs.

Photos: Nirmala Acharya.

Butternut (Cucurbita moschata)

Unlike acorn winter squash, butternuts exhibit greater tolerance to silverleaf disorder and WTV symptoms. While the plants may display low to moderate virus symptoms, their fruits remain unaffected by visible virus symptoms. As a result, fruits harvested from whitefly- and virus-infested plants remain marketable, making butternut squash a more resilient option for growers dealing with these challenges.

Therefore, we recommend planting butternut squash over all other long-season cucurbits because of its tolerance to silvering and WTV damage. The symptoms of silver leaf disorder, CYSDV, and CCYV mixed infection in butternut winter squash are shown in Figure 9.

Photos: Nirmala Acharya.

Calabaza (Cucurbita moschata)

Calabaza winter squash is more tolerant to silverleaf disorder and WTVs. Fruits show no signs of viral symptoms. Despite this tolerance, the overall productivity of the calabaza is not satisfactory in southern Georgia fall-season environmental conditions.

Kabocha (Cucurbita maxima)

Kabocha winter squash is highly susceptible to silverleaf disorder and moderately susceptible to CuLCrV. However, chlorosis and yellowing caused by CYSDV and CCYV single- and mixed-infection symptoms are severe in kabocha winter squash. In contrast, fruits show no signs of viral symptoms. Like calabaza, the overall productivity of the kabocha type is not satisfactory in southern Georgia’s fall-season environmental conditions.

Hubbard (Cucurbita maxima)

Like kabocha, the severity of silverleaf disorder in hubbard (Figure 10) is comparatively higher than in acorn-type squash and significantly greater than in butternut squash. They exhibit less-severe curling and crumpling symptoms from CuLCrV. They are moderately to highly susceptible to CYSDV and CCYV. Hubbard squash fruits harvested in the fall in southern Georgia show virus symptoms (Figure 10), making them unmarketable. Hubbard squash has poor overall productivity during the fall growing season in southern Georgia.

Photo: Nirmala Acharya.

Pumpkins

In pumpkin, the severity of silverleaf disorder symptoms (Figure 11A) differs among cultivars, ranging from moderate to high. Symptoms associated with single and mixed infections of CuLCrV, CYSDV, and CCYV are common, and mixed infections show more severe symptoms than single infections. Infection with CuLCrV alone results in crumpling, curling, chlorosis of newer leaves, and plant stunting in intense cases (Figure 11B), while a mixed infection of CuLCrV, CYSDV, and CCYV leads to crumpling, mosaic, yellowing, and stunting of the plant (Figure 11C).

In certain pumpkin cultivars, virus-infested fruits are susceptible to developing symptoms that compromise their marketability. The pumpkins harvested from the fall season in southern Georgia were unmarketable because of their small size, virus symptoms, and misshapen fruits. Pumpkin is the most negatively impacted long-season cucurbit crop by damage from silvering and WTVs. Overall, we do not suggest growing pumpkins in southern Georgia during the fall season because of virus pressure.

Photos: Nirmala Acharya.

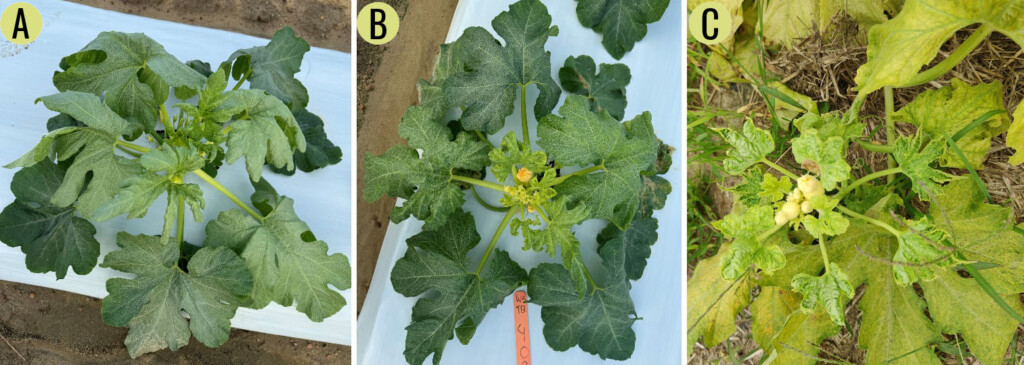

Watermelon

Like cucumbers, watermelon does not show symptoms of silverleaf disorder (Figure 12A). However, it is highly susceptible to CuLCrV, CYSDV, and CCYV. Like other cucurbits, infection with CuLCrV alone results in crumpling and curling of newer leaves (Figure 12B), while a mixed infection of CuLCrV, CYSDV, and CCYV leads to curling, crumpling, yellowing, and stunting of the plant (Figure 12C). Watermelons harvested from the fall season in southern Georgia are unmarketable because of their small size, misshapen fruits, and internal virus symptoms.

Photos: Nirmala Acharya.

Conclusion

Selecting the appropriate cucurbit crop, species, type, and cultivar is imperative to minimize yield losses from silverleaf disorder and whitefly-transmitted viruses. Among all short-season cucurbit crops, cucumbers are resistant to both silverleaf disorder and curling and crumpling symptoms caused by CuLCrV infestation. Among summer squash, zucchini is comparatively more tolerant of leaf silvering and WTV symptom severity compared to yellow squash. Butternut winter squash is comparatively more tolerant of whitefly and WTV infestation among long-season cucurbits.

In addition, the calabaza winter squash is tolerant of silverleaf disorder. Calabaza and kabocha winter squash fruits show no signs of viral symptoms. However, their overall productivity is unsatisfactory in southern Georgia’s fall-season environmental conditions. Pumpkins and watermelons are not suited for fall-season production in southern Georgia because of high viral-disease pressure and inappropriate environmental conditions.

Cucumbers and butternut winter squash are the most highly recommended short-season and long-season cucurbit crops that can perform well in fruit yield with moderate to high tolerance of whiteflies and WTV pressure, depending on cultivars.

References

Arshad, R., Joseph, S. V., & Hudson, W. (2023). Silverleaf whitefly: A pest in nursery and greenhouse ornamental crops (Publication No. C 1249). University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. https://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.html?number=C1249

Barman, A., Toews, M., & Roberts, P. (2023). Sampling and managing whiteflies in Georgia cotton (Publication No. C 1184). University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. https://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.html?number=C1184

Devendran, R., Kavalappara, S. R., Simmons, A. M., & Bag, S. (2023). Whitefly-transmitted viruses of cucurbits in the Southern United States. Viruses, 15(11), 2278. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15112278

Dutta, B., Myers, B., Coolong, T., Srinivasan, B., Sparks, A. N., & Bag, S. (2024). Whitefly-transmitted plant viruses in South Georgia (Publication No. B 1507). University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. https://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.html?number=B1507

Riley, D. G., & Roberts, P. (2020). Whiteflies [Fact sheet]. University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. https://ipm.uga.edu/files/2020/07/Whiteflies_2020.pdf

Sparks, A., Roberts, P., Barman, A., Riley, D., & Toews, M. (2018). Cross-commodity management of silverleaf whitefly in Georgia (Publication No. C 1141). University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. https://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.html?number=C1141

Thanks to Kayla R. Brenton for her contributions to the editing of this publication.