Thrips parvispinus (Karny) is an invasive insect pest that poses a serious global threat to vegetables and ornamentals in both fields and greenhouses. Originally from Asia, this species has spread to multiple regions around the world, including parts of Africa, Australia, Europe, and North America.

In the United States, T. parvispinus first became established in Florida in 2020 and has since been detected in other states, including Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Colorado, Michigan, and Wisconsin. This highly polyphagous (feeds on various kinds of plants) thrips species develops into large populations and disperses rapidly, causing extensive damage to the leaves, flowers, fruits, and shoots of plants. (Note that thrips is both the singular and plural noun for this insect.)

Identification

Adult T. parvispinus are small, slender insects with fringed wings that are difficult to detect without magnification.

Photo: Navdeep Kaur, University of Georgia.

Females are approximately 1 mm long, with dark brown to black bodies and light-colored legs and head. Their wings are pale near the base (Figure 1).

Photo: Navdeep Kaur, University of Georgia.

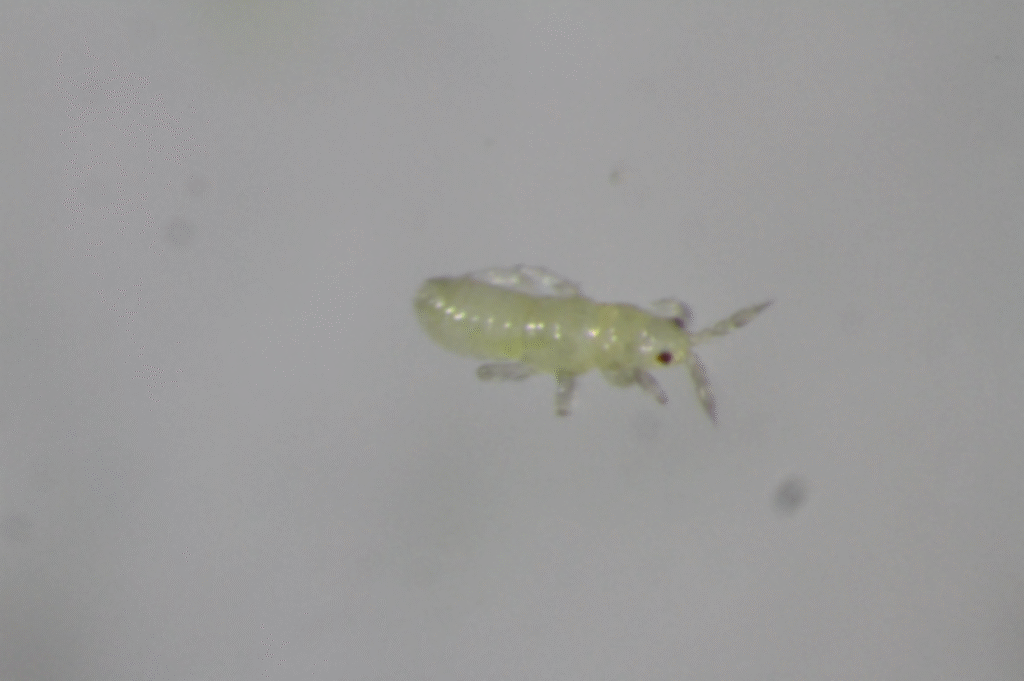

Males are entirely yellow and measure about 0.6 mm in length. The first instar larva is translucent white (Figure 2), while the second instar is pale yellow (Figure 3). These larvae feed on plant tissues for several days before pupating and emerging as adults.

Photo: Navdeep Kaur, University of Georgia.

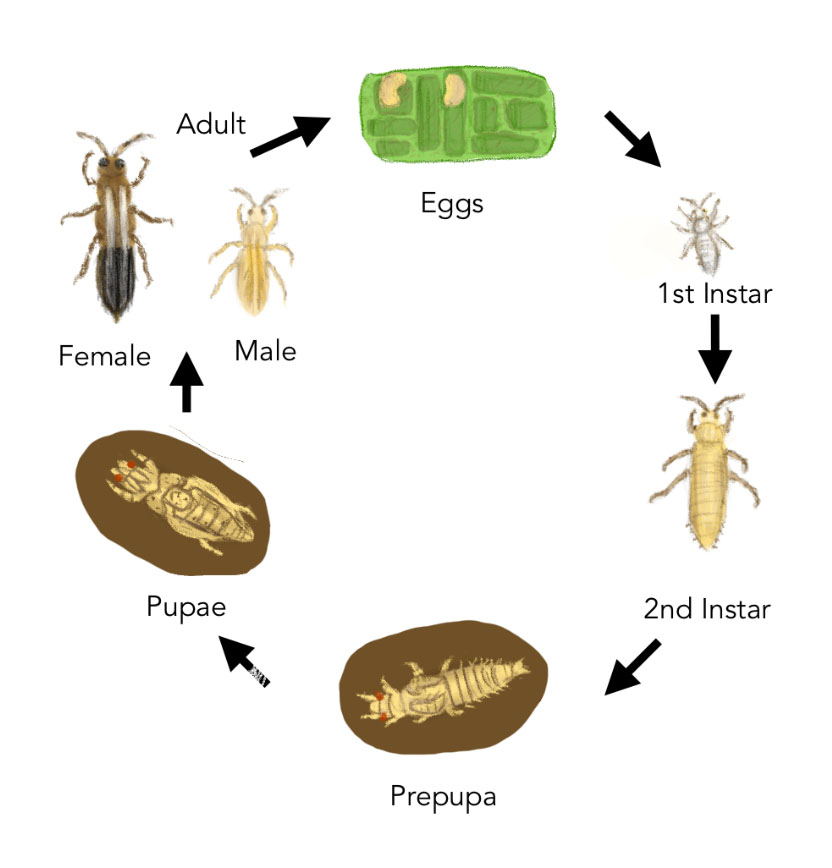

The life cycle of T. parvispinus consists of six stages: an egg, two larval stages, prepupa, pupa, and adult (Figure 4).

Illustration: Theresa Villanassery.

Females lay eggs—up to 15 eggs during their lifetime—by inserting them individually into leaves, petioles, bracts, petals, and developing fruits. They can complete their life cycle in about 15–17 days under optimal conditions (a temperature of 27 ± 1 °C and a relative humidity of 65% ± 5%), resulting in over 20 generations per year.

Various life stages overlap when the thrips population is high. Their short life cycle and rapid development enable them to cause serious damage in a short period of time.

Host Range

T. parvispinus has a wide host range, with approximately 100 plant species from 39 families worldwide. Notable vegetable hosts include peppers (Capsicum annuum), eggplants (Solanum melongena), cucumbers (Cucumis sativus), potatoes (Solanum tuberosum), and watermelons (Citrullus lanatus). Ornamental hosts include gardenia (Gardenia jasminoides), mandevilla (Mandevilla spp.), anthurium (Anthurium andraeanum), hoya (Hoya spp.), and chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum spp.).

Damage Symptoms

Thrips parvispinus use their rasping-sucking mouthparts to puncture plant cells and extract the cell contents. Larvae and adults both primarily feed on developing leaves, buds, and flowers.

Infested leaves exhibit light-colored spots that gradually turn brown or develop into silver scars (Figures 5A–D). Feeding damage leads to distorted growth, curled leaves, and premature defoliation (Figure 5E). Excessive stippling and scratches on the undersides of the leaves result in chlorosis from chlorophyll loss, which can sometimes progress to a yellow or reddish-brown coloration. At higher infestation levels, leaves may show a burned or scorched appearance (Figure 5A).

Photos: A–D. Navdeep Kaur, University of Georgia; E. Anna Mészáros, commercial vegetable Extension agent, University of Florida IFAS Extension, Palm Beach County.

Feeding on buds and flowers causes discoloration and deformation, reducing the yields of vegetables and the market values of ornamentals (Figure 6).

Photos: Anna Mészáros, commercial vegetable Extension agent, University of Florida IFAS Extension, Palm Beach County.

On fruits, thrips feeding results in scars and blemishes that compromise quality and marketability (Figure 7).

Photo: Anna Mészáros, commercial vegetable Extension agent, University of Florida IFAS Extension, Palm Beach County.

The symptoms may closely resemble damage from broad mites. Severe infestations can stunt plant growth and lower yield. Feeding damage also creates potential infection sites for secondary pathogens like the fungus Cladosporium.

Management Strategies

Monitoring and Scouting

Regularly inspecting plants, particularly new leaves and flowers, for signs of thrips damage is critical for preventing thrips populations from causing economic damage. Tapping plants over a white sheet of paper or tray helps dislodge thrips for easier detection using a hand lens or visor at 20X magnification. Yellow sticky traps placed at the plant canopy level at regular intervals throughout the crop also are effective for monitoring adult thrips populations.

Cultural Controls

Proper sanitation is essential for managing thrips. Infested plant material and weeds that can support thrips populations must be removed from the growing area and destroyed. For cutting propagation materials, use a clean, pest-free mother plant and apply preventative dips (e.g., insecticidal soap or horticultural oils) before planting. A follow-up dip of rooted cuttings during transplanting helps reduce the emergence of eggs or larvae that were not initially controlled.

Biological Controls

Several natural enemies have been assessed for managing T. parvispinus, with differing levels of success. The most effective biological control is using predatory mites like Amblyseius swirskii, Neoseiulus cucumeris, Amblyseius andersoni, and Amblyseius degenerans, which have shown significant effectiveness in controlling the first larval stage, with A. swirskii and A. degenerans also feeding on the prepupal stage. Anystis baccarum can consume the second larval stage, prepupae, and pupae. These mites are commercially available and can be applied preventively or at the beginning of an infestation.

Other beneficial insects, such as minute pirate bugs (Orius insidiosus), green lacewings (Chrysoperla carnea), and brown lacewings (Micromus variegatus), also have been used in integrated pest management programs. However, their effectiveness specifically against T. parvispinus varies, and further research is needed.

Implementing a biological control program requires careful monitoring and often is used with other management strategies to achieve the most effective results.

Chemical Controls

Chemicals reported to be effective at managing T. parvispinus include products containing the active ingredients acephate (IRAC Group 1B), abamectin (Group 6), chlorfenapyr (Group 13), spinosad (Group 5), sulfoxaflor-spinetoram (Group 4C and 5), acetamiprid (Group 4A), cyclaniliprole (Group 28), novaluron (Group 15), and pyridalyl (Group UN; these are compounds with unknown or uncertain modes of action). Additionally, insecticides such as flupyradifurone (Group 4D) and cyantraniliprole (Group 28) have shown promising results, especially for ornamental crops. Chlorfenapyr and pyridalyl are only registered for use in greenhouses, while the remaining active ingredients are registered for use in nurseries and greenhouses.

Biorational products, such as 3% mineral oil and sesame oil, can also be integrated into management programs, providing alternative controls with reduced nontarget impacts. However, because of the high reproductive rate and potential for resistance development in T. parvispinus, it is crucial to rotate insecticides with different modes of action (as classified by IRAC). When using chemicals, always follow label instructions and consult your local Extension service for region-specific recommendations.

References

Ahmed, M. Z., Revynthi, A. M., McKenzie, C. L., & Osborne, L. S. (2024, March 12). Thrips parvispinus (Karny), an emerging invasive and regulated pest in the United States. Retrieved May 2, 2025, from https://mrec.ifas.ufl.edu/lsolab/thrips/thrips-parvispinus/

Ataide, L. M. S., Vargas, G., Velazquez-Hernandez, Y., Reyes-Arauz, I., Villamarin, P., Canon, M. A., Yang, X., Riley, S. S., & Revynthi, A. M. (2024). Efficacy of conventional and biorational insecticides against the invasive pest Thrips parvispinus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) under containment conditions. Insects, 15(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects15010048

Joseph, S. V. (2023, April 24). Watch for Thrips parvispinus in Georgia. UGA Turf and Ornamental Pest Management blog. Retrieved May 2, 2025, from https://site.caes.uga.edu/entomologyresearch/2023/04/watch-for-thrips-parvispinus-in-georgia/

Pijnakker, J. (2023, November 22). Thrips parvispinus (tobacco thrips). CABI Compendium. https://doi.org/10.1079/cabicompendium.53744

Prade, P. (2024, May 22). Invasive insect: Thrips parvispinus. PennState Extension. Retrieved May 2, 2025, from https://extension.psu.edu/invasive-insect-thrips-parvispinus