The blueberry gall midge is considered a serious pest of blueberries in Georgia, and reports of infestations have become increasingly common in recent years. The damage caused by this midge can reduce the growth and productivity of plants, and repeated infestations can leave blueberry bushes with sparse foliage. Rabbiteye blueberries are more susceptible to this type of damage than highbush types.

Identification and Biology

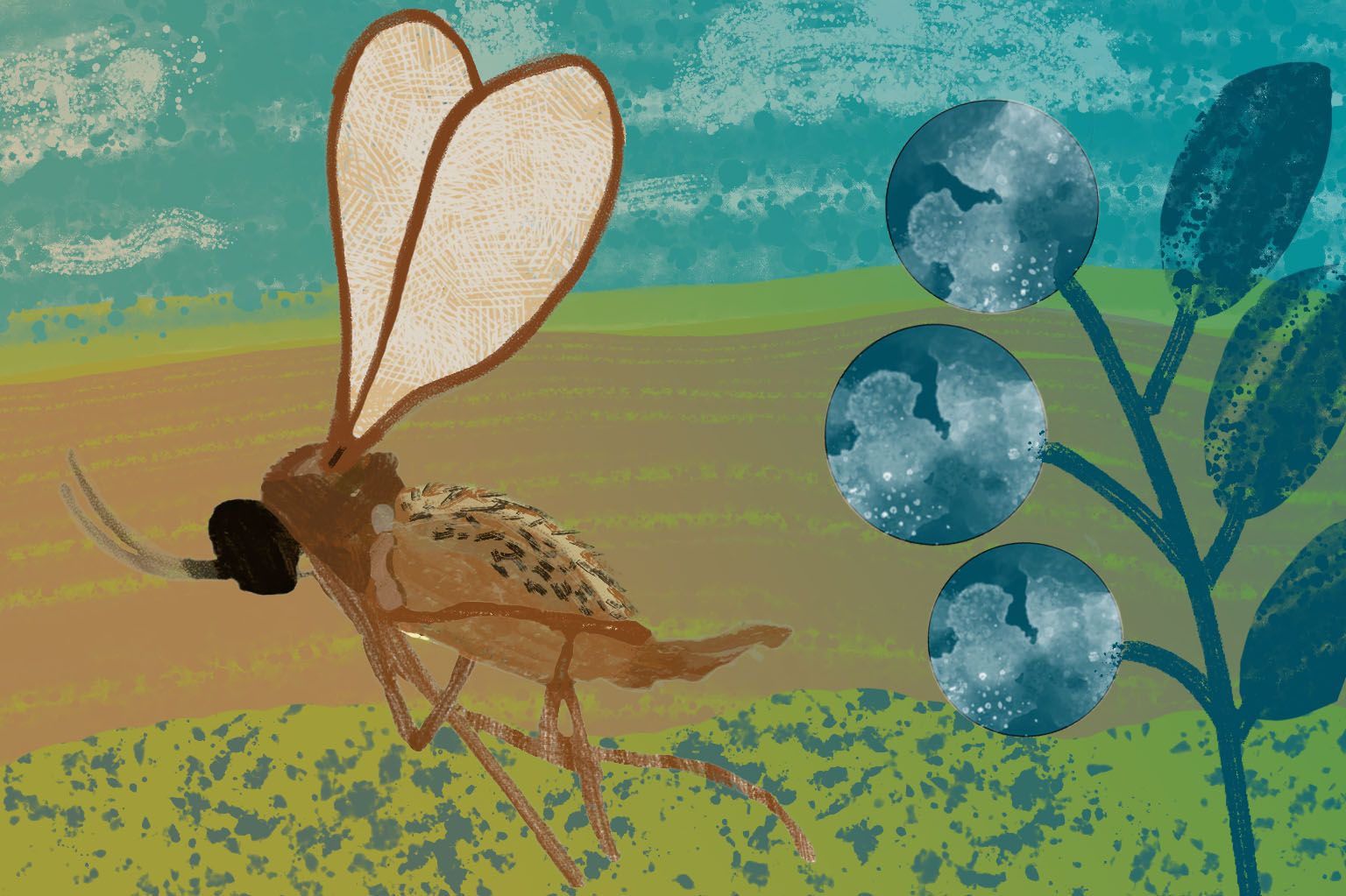

Blueberry gall midge, Dasineura oxycoccana (Johnson), is a small fly that is native to North America. Adults are 2–3 mm in length. Their wings have a fringe of hairs on the hind edge (Figure 1). Adults live just a few days, only long enough to mate and lay eggs.

Females produce a pheromone to attract males. Eggs are laid within a plant host. The eggs are oval-shaped, transparent, and very small. Larvae are legless and less than 3 mm long (Lyrene & Payne, 1995). Newly hatched larvae are white in color and become orange by the time they are ready to pupate (Figure 2).

Mature larvae have a unique feature—a dark, hardened structure shaped like a “T” on the underside near the head. They drop to the ground and pupate in the soil.

Little is known about where blueberry gall midges overwinter or which other plant hosts they can feed on. Most likely, they overwinter as pupae in the soil, emerging as adults early in the year when blueberry buds start to break.

Pest Status

The blueberry gall midge was first identified as a pest of rabbiteye blueberry (Vaccinium ashei) in the southeastern U.S. (Lyrene & Payne, 1992). It is now recognized as a pest of all cultivated Vaccinium species: highbush blueberry, rabbiteye blueberry, lowbush blueberry, and cranberry. It is also known as the cranberry tipworm. There is evidence, however, that the midges infesting blueberry and cranberry are separate species (Mathur et al., 2012).

Historically, blueberry gall midge has not been a serious problem in Georgia blueberries, but over the past few years, reports of midge infestations have become common (Sial & Jacobs, 2017).

Blueberry Gall Midge Damage and Monitoring

Blueberry gall midge females lay eggs in developing flower and leaf buds (Dernisky et al., 2005). Many eggs can be found in a single bud. Larvae feed within the buds, reducing flower production and potential yield.

Dormant buds (Stage 1) are too tightly packed for blueberry gall midges to lay eggs between the scales. Stages 2 and 3, however, are vulnerable (Dernisky et al., 2005). Later bud stages are too open to provide shelter for eggs and newly hatched larvae.

Flower bud damage (Figure 3a & 3b) can be mistaken for frost damage, so monitoring for this pest is extremely important (Lyrene & Payne, 1992).

Monitoring methods include emergence traps, panel traps, and bud sampling (Rhodes et al., 2014). Emergence traps and panel traps are designed to catch adult midges near blueberry bushes. Bud sampling is the only way to confirm the presence of larvae in buds.

For bud sampling, collect five young buds from 10–15 randomly selected bushes per acre. Place the buds into a zipper storage bag at room temperature. If buds are infested, reddish-orange larvae will begin to emerge after 3–4 days (Figure 4).

Damage to leaf buds can affect plant vigor. If the apical growing tip is killed (Figure 5), plants will produce more lateral growth.

Continual infestation and destruction of the vegetative growing tips will result in sparse foliation (Lyrene & Payne, 1992). Rabbiteye types are more susceptible to this type of damage than highbush.

Management of Blueberry Gall Midge

Blueberry gall midges are naturally suppressed by predators and parasitoids and generally do not require management. Multiple species of parasitoid wasps have been observed attacking blueberry gall midge (Sampson et al., 2002, 2006, 2013). These wasps can find the larvae within buds and sting them (Figure 6).

It’s challenging to use chemical controls on blueberry gall midge because eggs and larvae are well protected inside the buds. Insecticide sprays need to be timed to target adult midges before they have a chance to lay eggs. In fields with a history of blueberry gall midge infestation, preventative insecticide applications are needed to protect Stage 2 buds.

Effective insecticides include diazinon, Delegate®, Entrust®, Imidan®, malathion, and Assail®. Of these, Entrust is the only product approved for use in organic systems, and it is also the main product used in organic management of spotted-wing drosophila. Therefore, growers should pay special attention to the label restrictions on the amount of Entrust that can be applied per year. For specific questions, consult your local Extension agent.

References

Dernisky, A. K., Evans, R. C., Liburd, O. E., & Mackenzie, K. (2005). Characterization of early floral damage by cranberry tipworm (Dasineura oxycoccana Johnson) as a precursor to reduced fruit set in rabbiteye blueberry (Vaccinium ashei Reade). International Journal of Pest Management, 51(2), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/09670870500130980

Lyrene, P. M., & Payne, J. A. (1992). Blueberry gall midge: A pest on rabbiteye blueberry in Florida. Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society, 105, 297–300.

Lyrene, P. M., & Payne, J. A. (1995). Blueberry gall midge: A new pest of rabbiteye blueberries. In R. E. Gough & R. F. Korcak (Eds.), Blueberries: A century of research (pp. 111–124). Haworth Press, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1300/J065v03n02_12

Mathur, S., Cook, M. A., Sinclair, B. J., & Fitzpatrick, S. M. (2012). DNA barcodes suggest cryptic speciation in Dasineura oxycoccana (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) on cranberry, Vaccinium macrocarpon, and blueberry, V. corymbosum. Florida Entomologist, 95(2), 387–394. https://doi.org/10.1653/024.095.0222

Rhodes, E. M., Benda, N. D., & Liburd, O. E. (2014). Field distribution of Dasineura oxycoccana (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) adults, larvae, pupae, and parasitoids and evaluation of monitoring trap designs in Florida. Journal of Economic Entomology, 107(1), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1603/EC13409

Sampson, B. J., Rinehart, T. A., Liburd, O. E., Stringer, S. J., & Spiers, J. M. (2006). Biology of parasitoids (Hymenoptera) attacking Dasineura oxycoccana and Prodiplosis vaccinii (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) in cultivated blueberries. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 99(1), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1603/0013-8746(2006)099[0113:BOPHAD]2.0.CO;2

Sampson, B. J., Roubos, C. R., Stringer, S. J., Marshall, D., & Liburd, O. E. (2013). Biology and efficacy of Aprostocetus (Eulophidae: Hymenoptera) as a parasitoid of the blueberry gall midge complex: Dasineura oxycoccana and Prodiplosis vaccinii (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae). Journal of Economic Entomology, 106(1), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1603/EC12404

Sampson, B. J., Stringer, S. J., & Spiers, J. M. (2002). Integrated pest management for Dasineura oxycoccana (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) in blueberry. Environmental Entomology, 31(2), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1603/0046-225X-31.2.339

Sial, A. A., & Jacobs, J. (2017, January 19). Monitoring and management of blueberry gall midge. UGA Blueberry Blog. https://site.caes.uga.edu/blueberry/2017/01/blueberry-gall-midge-3/