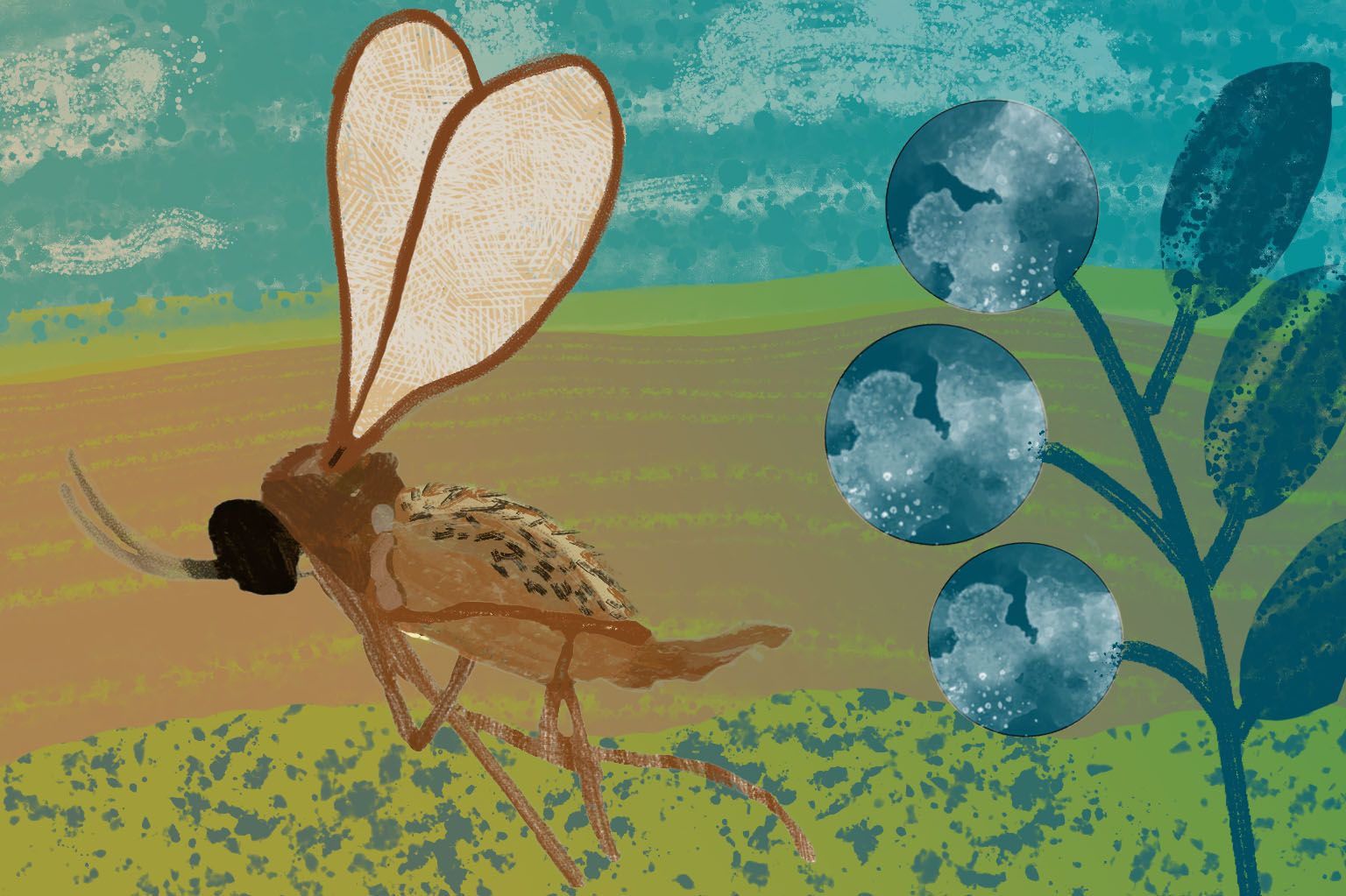

European hornets (Vespa crabro) are widespread across much of the eastern U.S. (Figure 1).

Photo: Shimat V. Joseph, University of Georgia.

Native to Europe and Asia, they were accidentally introduced to North America in the mid-1800s. The European hornet is the largest species found in the United States and is particularly common in Georgia. It is also known as the brown or giant hornet. In 2019, the invasive, northern giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia) was discovered in the state of Washington, and in 2023, the invasive, yellow-legged hornet (Vespa velutina) was discovered in Georgia around Savannah (Figure 2).

Photos: Hanna Royals, Museum Collections: Hymenoptera, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org.

Description

Adult European hornet workers are approximately 1 in. long and have black and yellow stripes on their abdomen (Figure 1). The black stripes have three downward extensions, and some appear as teardrops. The queens of European hornets grow to 1.3 in. in length and are reddish-brown with yellow stripes. The heads of European hornets are hairy and reddish-brown, although the redness fades on the face, becoming yellowish-brown.

European hornets primarily build nests in hollow trees or on bark, using fiber they collect from the tree bark (Figure 3).

Photo: Aaron Edmonds.

Nests are typically found in woodlots, but they occasionally construct nests in barns and sheds, as well as in attics and wall voids of houses near wooded areas. They prefer dark areas for building nests. From the outside, European hornet nests resemble gray paper coverings made from decayed wood fibers. The nest is smaller in size in the spring or early summer but eventually increases in size as the season progresses. There are approximately six to eight combs within a finished nest in the fall.

European hornets are active at night and are attracted to lights. They are predatory and feed on other insects, but they do not aggressively attack bees.

Life Cycle

Upon emerging from their overwintering sites in the spring, queens build a small nest. Inside these newly constructed nests, queens lay eggs and raise workers. Once a colony has enough workers, they take over the task of nest-building.

A queen can lay approximately 500 eggs in total, dedicating her entire time to this task, thus increasing the worker population within the colony. All workers are females (sisters), but they are sterile.

Workers are responsible for foraging, caring for the young, nest-building activities, and defending the nest from intruders. There are about 800–1,000 workers in a mature (full) nest.

By the fall, each colony produces a group of reproductively active males and females, which become kings and queens, respectively. They mate in the fall, and the mated queens overwinter, while males and all workers die by the end of the year as temperatures dip below 33 °F. The queens overwinter in natural sites, such as under bark and in tree hollows, or in man-made structures like attics. Every year, the mated queen builds a new nest in spring and does not reuse nests from previous years.

Damage

European hornet workers collect sap from the wounds they create on tree bark (Figure 4).

Photo submitted by a Clayton County resident.

They girdle the stem by removing the bark (Figure 5), which causes the branch or twig beyond that point to die.

Photo: Shimat V. Joseph, University of Georgia.

Occasionally, they chew and strip the bark from the tree (Figure 6) and use some of the fiber for nest construction. The damage is more severe in the fall when the number of workers reaches its maximum.

Photo: Louis-Michel Nageleisen, Département de la Santé des Forêts, Bugwood.org.

Host Plants

Attacks from European hornets are reported on several shrub or tree species, such as boxwood (Buxus sempervirens), birch (Betula spp.), dogwood (Cornus spp.), ligustrum (Ligustrum vulgare), lilac (Syringa vulgaris), rhododendron (Rhododendron spp.), poplar (Populus spp.), viburnum (Viburnum lepidotulum), and willow (Salix spp.).

Management

The best strategy for managing European hornets is to eliminate the nest. However, locating the nest is often difficult. Since hornets can also build nests inside wall voids, those areas should also be inspected.

Once the nest is found, it is advisable to seek professional help for its removal. Do not close the entrance of the nest. Stings from European hornets can be painful and may cause severe allergic reactions; in some cases, seeking medical attention is necessary. The stinger (ovipositor) is not left behind after a sting, like with honeybees, allowing hornets to sting multiple times. Generally, they are not aggressive, but may attack if they perceive a threat to their nest.

European hornets can be managed by spraying insecticide directly onto the nest. Many aerosol products, referred to as “wasp and hornet” sprays, are available. Because these aerosols can project insecticide approximately 15 ft, the applicator may not need to be very close to the nest for effective spraying.

The best time to apply insecticide is in the evening, just before sunset. Reapplication may be required if the number of workers is not reduced with the first application. Please wear the proper personal protection equipment (PPE) as outlined on the insecticide label before spraying. PPE is required during the nest removal.

Bifenthrin can be applied to the trunk to reduce the feeding activity of worker insects. It is effective only if there is noticeable feeding activity on the bark or sap. Please read the insecticide label thoroughly before applying it.

A dust formulation of insecticide can be applied at the entrance of the nest, as it carries residues into the colony and affects other workers within the colony. For more information, contact your county Extension agent.

References

Day, E., & Dellinger, T. A. (2023). European hornet (Publication No. 2911-1422; ENTO-576NP). Virginia Cooperative Extension. https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/2911/2911-1422/2911-1422.html

European hornet. (2024). PennState Extension. https://extension.psu.edu/european-hornet

Shaw, F. R., & Weidhaus, J., Jr. (1956). Distribution and habits of the giant hornet in North America. Journal of Economic Entomology, 49(2), 275. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/49.2.275

Smith-Pardo, A. H., Carpenter, J. M., & Kimsey, L. (2020). The diversity of hornets in the genus Vespa (Hymenoptera: Vespidae; Vespinae), their importance and interceptions in the United States. Insect Systematics and Diversity, 4(3), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/isd/ixaa006